I’m currently trying to clear as many short books as I can off of my Unread Shelf before taking that picture tomorrow, but I’m willing to take it on faith that none of them are going to blow me away, and if they do, well, under the “My Blog, My Rules” rule, I can include them next year if I have to. This is the thirteenth year I’ve done this list, and the fifth time I expanded the list to 15– the shortlist was 28, and the first cull took it down to 15, then I took that down to 10 and then thought about it some more and decided to do 15 anyway. I surprised myself with a couple of these books, honestly; we’ll see what y’all think.

As always, “new” means “new to me,” not “released in 2025,” although the majority of at least the fiction books were 2025 releases and at least one of the nonfiction releases was as well. The oldest book on the list is from 1999.

Also as always, don’t read too much into specific placements. I spend a lot more time thinking about whether books should be on the list at all than where they should be on the list, and if I put this together again tomorrow without looking at it I doubt they’d be in the exact same order.

The twelve previous lists:

- The Top 15 New(*) Books I Read in 2024

- The Top 11 New(*) Books I Read in 2023

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2022

- The Top 15 New(*) Books I Read in 2021

- The Top 15 New(*) Books I Read in 2020

- The Top 15 New(*) Books I Read in 2019

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2018

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2017

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2016

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2015

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2014

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2013

And let’s do this:

15: The Stationery Shop, by Marjan Kamali. I went back and forth several times about whether this book or Kaveh Akbar’s Martyr! were going to be #15, nearly expanded the list to 16 books, then decided that I remembered The Stationery Shop a lot better and that should make the difference. You’re going to see a theme reading through this list; the quality of the book matters to getting on the shortlist, but going from the shortlist to the final 15 really depends on how much recall of the book I have, which isn’t always perfectly correlated with how much I enjoyed the book when I first read it. At any rate, this is a historical fiction and a love story and it borders on hated litratcher, beginning in Tehran in the 1950s just before the coup that installed Mohammed Reza as leader of Iran. The main character is a young woman whose engagement to a revolutionary is derailed by the coup, and the book bounces back and forth between various periods in her life as she eventually moves to America for college and marries another man. This will hit you in the gut if you ever feel like you lost anyone; the emotional bleed-through from Roya’s grief and loss over the course of the story is intense.

14: Agrippina: The Most Extraordinary Woman of the Roman World, by Emma Southon. I wanted to read more nonfiction this year, and I read a lot of good history in particular this year. Agrippina succeeds on several levels; Roman history can be excruciatingly complicated and dense (Southon riffs on their penchant for reusing names repeatedly) and a lot of the histories I’ve read of the Empire ended up really dry even if they didn’t want to be. This book is both a good biography of one of the more well-attested women in the ancient world and a good general history of Rome, and Southon’s salty sense of humor easily carries the book through what be a significantly trickier read in lesser hands. My only regret is that the book lost its original title in transition to paperback; it was originally subtitled Emperor, Exile, Hustler, Whore, but the publishers apparently rebelled after the hardcover edition came out and forced a name change. If you ever spot the original book in a used bookstore or anything like that for less than $75, please grab one for me. I’ve seen them listed for up to $300, but I don’t want it that much.

13: The Enchanted Greenhouse, by Sarah Beth Durst. This will be the first and only appearance of the phrase cozy fantasy on the list and the first but probably not the last appearance of the word delightful. This is the second of Sarah Beth Durst’s books that I’ve read, and while it’s not precisely a sequel to The Spellshop, it’s set in the same world and alludes to a lot of the same events– in fact, the book begins when the main character brings a spider plant to sentience, and said talking spider plant was one of the main characters in Spellshop. It may not surprise you to learn that the book is about an enchanted greenhouse, and that the main plot of the book involves threats to the plants in said greenhouse. This is cozy fantasy! The stakes are not high. The worst thing that could happen in this book is that a bunch of plants might die, and spoiler alert: the plants are not going to die. Terlu Perna is not much of a botanist and not much of an enchanter, however, and watching her and the hunky greenhouse guy she’s found herself inadvertently imposing upon (it’s a long story) try to figure out why the greenhouse is failing and how to fix it is a lot of fun. I’m going to keep reading this series as long as Sarah Beth Durst keeps writing them.

12: His Face is the Sun, by Michelle Jabès Corpora. When I reviewed this in July– brief pause to be surprised it was only July— I called it “#1 with a bullet” on my shortlist. So why is it all the way down at #12? To be honest, I had to stare at the cover for a minute to remember much about it. This feels unfair to the book, because I remember saying that, and it’s not like I’m not rereading my own reviews in preparing this list, but other than “Man, I really liked this book,” and a vague idea that it was set in Not Egypt, I couldn’t remember a damned thing about it. I’m definitely rereading it when the sequel comes out, because I’m not about to let my shitty recall screw up future books. This is a multi-POV book with characters ranging from child of Pharaoh to a farmer’s daughter to a young priestess who sees visions, and the characters interact with each other fascinatingly, popping in and out of each other’s lives over the course of the story. In my defense, even July was a hundred damn books ago. It’s possible that I read too much. Oh, and there’s a cat who sort of serves as a frame character to the entire book. I liked the cat an awful lot. The cat had better be in Book 2.

11: Capitana, by Cassandra James. Man, Goodreads really doesn’t like this book– the average review over there is 3.28, which in Goodreads terms may as well be a zero. Why? Apparently Cassandra James said some stuff, and I’m deliberately not going to find out What Kind of Stuff She Said because that would violate my Don’t Want None Won’t Be None rule. If I hadn’t noticed the low score and decided to wander through a couple of the reviews over there I wouldn’t be aware that the author is Considered Problematic, so I’m not going to worry about it and just tell you that this book is about a pirate hunter who turns pirate, and really, that’s generally all I’m going to need to enjoy a book? I like books about pirates. There’s a romantasy element to it, but it’s not overwhelming, and main character Ximena really does need a few things beaten into her head a couple of times before she actually believes them, but she’s also supposed to be seventeen, and … well. I’m well accustomed to the idea that sometimes teenagers have to be told things or be exposed to certain ideas multiple times before they sink in. Feel free to look into James if you’re worried about supporting whatever kind of person she’s going to turn out to be; Illumicrate sent me this one blind, and I enjoyed it, and now it’s on the list.

10: Hammajang Luck, by Makana Yamamoto. Speaking of “books Illumicrate sent me,” this one also would never have crossed my radar if I didn’t have a subscription to that service, and speaking of “you had me at the premise,” it’s a Hawaiian-inflected cyberpunk lesbian heist novel set on a space station, and what that means is that if I’d encountered it on my own it would have been an instant buy regardless. There are shifting loyalties and betrayals and an ending that took me completely by surprise and I had an enormous amount of fun reading this. I’m still not sure if this is a one-shot or if there are more planned, but Makana Yamamoto went directly onto my “buy immediately” list after reading this. “Hammajang,” by the way, is Hawaiian Pidgin for “messy” or “chaotic” or maybe “fucked-up” if you’re feeling salty; there’s going to be a decent amount of unfamiliar vocabulary sprinkled throughout this one, if I remember correctly, so be prepared for that. Future Space Station Hawai’i isn’t as nice a place as the original, but it’s awesome to read about.

9: The Bone Raiders, by Jackson Ford. This one was originally not on my shortlist, and I looked at my shortlist and thought “Where the hell is The Bone Raiders?” and added it and then it ended up in the top 10. I will reiterate what I said in my original review: please judge this book by its cover. Five badass women of color with a dragon. Okay, it’s not a dragon, but it might as well be a dragon. It’s dragon-adjacent. You are absolutely getting the book you think you are getting from looking at this cover, and I don’t want to beat the phrase “right up my alley” to death in this piece, but … yeah. The band of titular Raiders are called the Rakata, and Genghis Khan isn’t the bad guy but close enough, and damn near every POV character in the book is a woman. This one is definitely book one of a trilogy; the final chapter leads directly into the next book. This book also has the distinction of being more concerned about animal husbandry than anything else on the list. It turns out that’s a plus. I’d never really considered “does this book involve animal husbandry?” before choosing to read something before, but I’m definitely starting now.

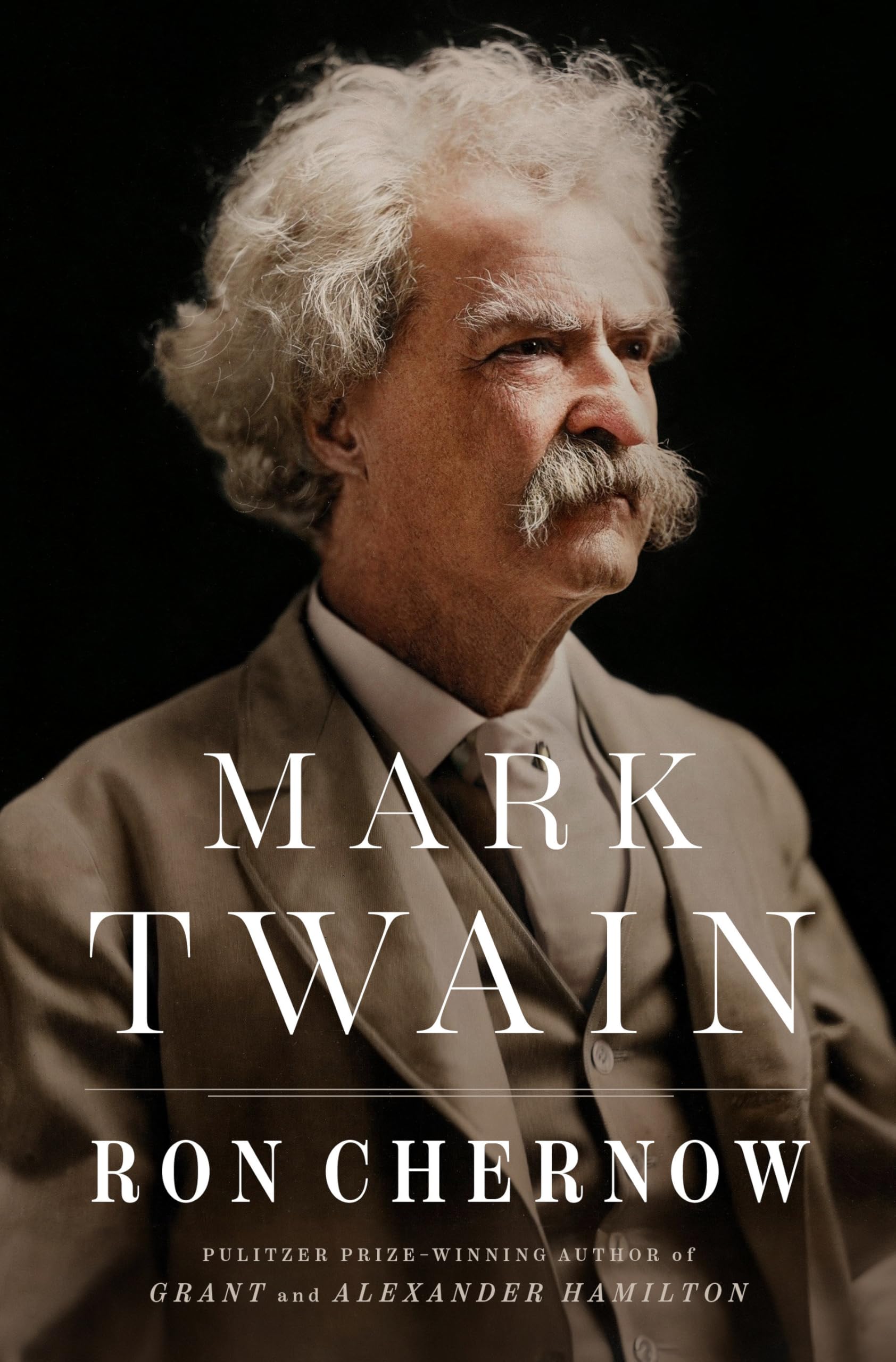

8: Mark Twain, by Ron Chernow. Here’s where we enter the And now, for something completely different phase of the list: Ron Chernow is a known quantity around here; I have read his biographies of George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, and I keep getting surprised by the fact that I haven’t read his biography of Ulysses S Grant. He writes giant doorstops — Twain is 1200 pages — and despite that his books are still quick, propulsive reads. I have to admit that I came away from this book with a slightly lower opinion of Mark Twain as a person than I did going into it, but the book itself is magnificently well-done. I didn’t review the book after I read it, but I did review Mark Twain himself, who gets 3/5 stars as a human being. Writing biographies of authors can be really tricky, as authors don’t necessarily tend to do a whole lot beyond, y’know, writing stuff, but Twain was enough of a world traveler and general hob-knobber of famous people that the book never devolves into “he wrote this, and then he wrote that,” and instead can focus on things like his absolutely absurd number of failed business ventures and his odd obsession with young girls. Which … yeah. Three out of five for Twain. At best.

7: The Faithful Executioner: Life and Death, Honor and Shame in the Turbulent Sixteenth Century, by Joel F. Harrington. This one is a biography-but-not-really, of a Nuremberg executioner named Frantz Schmidt. Schmidt left a priceless historical record behind: he carefully wrote down forty-five years of details about the three hundred and sixty-one people he put to death and hundreds more who he tortured or disfigured as an agent of the Imperial City of Nuremberg. He also had a medical practice, as it turns out public executioner wasn’t enough to pay the bills even in the late 1500s. The reason I can’t really call it a biography is that the journal itself didn’t have a ton of details about Schmidt himself, so the book tells us what it can and then pivots to being a history of sixteenth-century Nuremberg and the profession of executioner in general, dipping its toe into Renaissance-era legal theory and criminal justice. The book is chock full of little details that will surprise you– did you know that most executions with swords were carried out with the victim sitting in a chair, for example? — and as I don’t know a ton about the Renaissance era in general, particularly in what would eventually become Germany, so there was a lot to learn here.

6: Galileo’s Daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith and Love, by Dava Sobel. Hey, look, a theme! Galileo’s Daughter is also a history from the fifteenth century drawn mostly from the writings of its main character, and is also a book that isn’t quite a biography of the person it’s supposedly named after. Perhaps a third of this book is concerned with Suor Maria Celeste, the second of Galileo’s three illegitimate children and the one he had the closest relationship with. Suor Maria was sent to a convent by her father at a young age, but stayed near him for most of his life and exchanged an enormous corpus of letters, from which this book is drawn. You probably won’t be surprised to learn that the book is mostly actually about Galileo through the eyes of his immensely intelligent and doting daughter; you get the feeling that had Suor Maria been born four hundred years later she’d have been a famous intellectual giant on her own terms. Much like The Faithful Executioner, you also get a lot of information about the Italian Renaissance, and again, European history isn’t one of my strong points, so Sobel’s deft hand with her topic was greatly appreciated. This book got recommended to me enthusiastically a couple of years before I finally got around to it; I shouldn’t have waited so long.

5: The Reformatory, by Tananarive Due. I need to treat Tananarive Due with more respect; I keep being surprised by how much I enjoy her books, and then forgetting how much I enjoyed them later. Well, damn it, The Reformatory is awesome, and I can imagine a world where I put it higher in the top five than it is right now. It’s a historical fiction and a horror story; set in 1950 in Florida, the main character is Robert Stephens Jr, a 12-year-old Black boy who kicks an older white boy who is harassing his sister and is sent to the Gracetown School for Boys, a so-called “reform school” run by an absolute monster of a human being. His sentence is supposedly six months, but everyone knows that anyone sent to Gracetown isn’t getting out before their 21st birthday if they ever get out at all; they will simply find excuses to keep the kids imprisoned for as long as they want them there. This is already a horror story before you get to the ghosts, is what I’m saying, and … well, you can probably imagine that any ghosts sticking around at a reform school are not going to be the happy friendly type. The book bounces back and forth in POV between Robert and his sister, who is doing her best to get him away from Gracetown and is stymied at every opportunity. There are a ton of twists and turns and I enjoyed this one enormously.

4: Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers our Lives, by Siddharth Kara. This book wasn’t precisely recommended to me; I found it lying on a countertop at my brother’s house and picked it up and before I knew it there was another copy on its way to my house. The Reformatory started what’s going to be four horror books in a row; Cobalt Red is the scariest, by a long shot, as it’s nonfiction and everything discussed in it is absolutely terrible. So, it turns out that cobalt is essential to every lithium-ion battery on the planet, right? And 75% of the world’s supply of cobalt comes from the Congo. And unfortunately you will probably not be surprised to learn that said cobalt is mined under fucking awful conditions, largely by hand and frequently by children, and that very little of the wealth generated by the Congo’s cobalt actually makes its way back to the Congolese. If you’ve ever read Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost, you can consider this book an unofficial sequel to it, as the way modern companies and multinational corporations are strip-mining the Congo and enslaving the Congolese to do it is not especially different from the way Belgian colonizers were exploiting the Congo for its rubber and other natural resources a century and a half ago. This book will make you feel awful, and then you won’t do anything about it, and that will make it worse. Read it.

3: The Eyes are the Best Part, by Monika Kim. This excellent little horror debut was another book box find– not Illumicrate this time, but Aardvark, although once I’d read it I discovered that Illumicrate had their own edition of it and immediately ordered that one too. I called this “deliciously, delightfully fucked-up” in my review, and I absolutely stand by it. Eyes is about a college-aged Korean-American woman named Ji-Won, who lives at home with her family. Early in the book her father abruptly deserts his wife after having an affair, and the rest of the book is equal parts psychological horror, body horror and political indictment of a certain kind of white fetishism about Asian women, as both Ji-Won and her mother attract the attention of men who are terrible in related but different ways and Ji-Won herself suffers a mental break and basically becomes a serial killer. The eyes referred to in the title are fish eyes; there’s a deeply squicky bit at the beginning where her mother waxes poetic about how delicious fish eyes are and Ji-Won, born in the States, isn’t able to bring herself to try them. It, uh, doesn’t last. You’ll need a strong stomach to get through this one, I think, but it’s well worth it.

2: You Weren’t Meant to be Human, by Andrew Joseph White. It is possible that if you’re a regular reader and have a decent memory that this one is surprising, as my initial review of this book wasn’t wholly positive. But remember earlier, two thousand or so words ago, where I said that how a book sticks around for me is almost as important as what I think when I first read it? Because You Weren’t Meant to be Human has crawled into my brain and lives there permanently now. I’ve recapped my own reviews repeatedly through this piece but I’m going to directly quote myself here:

Y’all, I’m okay with it if I never read another body horror again. I’m good. I’m happy with naming this book the pinnacle of the genre and then never touching it again. This is one of the most brutal and harrowing books I’ve ever read and has one of the most shocking and grotesque endings I’ve ever seen … and I did not enjoy one single second of reading it.

That’s still one hundred percent true. You should absolutely go read my original review before you pick this one up if you’re curious, because it needs every single one of the trigger warnings before you read it, and I do not blame you one bit if you read my review and decide it’s not for you. I’m not even sure it’s for me, and this is also a book where I got a special edition right after reading my Aardvark copy, although in this case it was part of the regular subscription and not one I picked on my own.

This book is fucked up, and it’ll fuck you up, and it fucked me up, and as I’ve gotten farther away from it I’ve lost a little bit of my original “God, no” reaction to it and just come to appreciate the sheer amount of craft necessary to write it in the first place. It’s simultaneously one of the best books I read this year and easily the least enjoyable. Do with that what you will.

And finally …

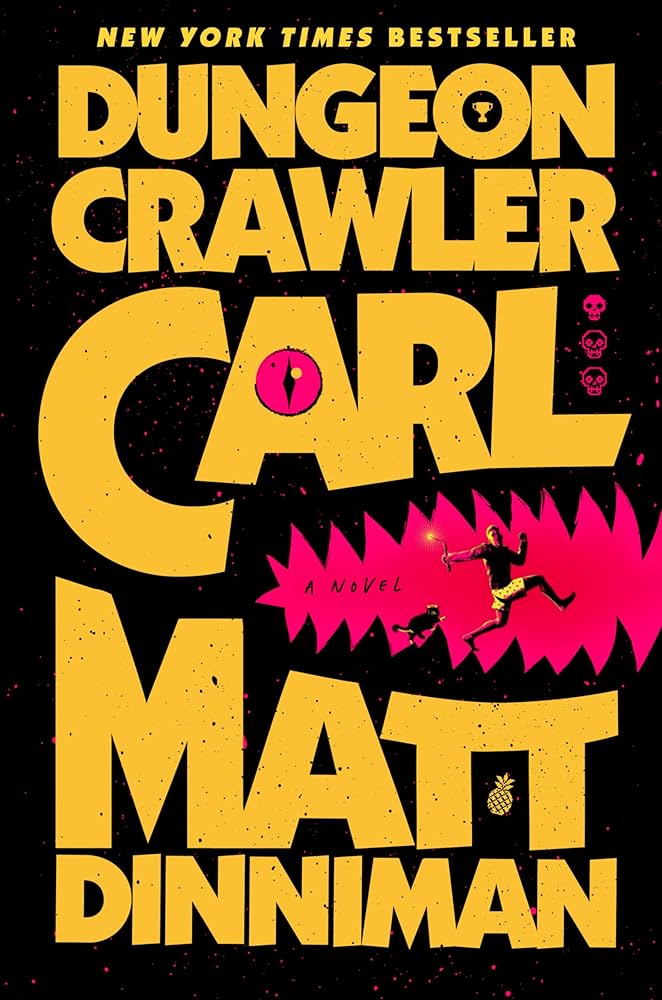

1: Dungeon Crawler Carl, by Matt Dinniman.

Oh, shut up.

I’m cheating here a little bit. The Dungeon Crawler Carl series is currently on Book Seven, with Book 8 due out next year and at least two more planned to follow after that. I read all seven of them in 2025, and of the seven, the last three all made the shortlist. I suppose if you put a gun to my head I could put This Inevitable Ruin here and not the first book, but we’re going to go with using the first book as a stand-in for the entire series. My blog, my rules, dammit.

I understand the people who have resisted this series, I genuinely do. The idea that there are seven books and probably at least six thousand pages about some random dude and his talking cat who get sucked into an intergalactic role-playing game after Earth is invaded and mostly destroyed, with leveling and magic and weapons and ability scores, and that their job is to fight through successive levels of an actual dungeon cobbled together from the ruins of Earth for the televised enjoyment of the rest of the sentient species of the universe, is so fundamentally ridiculous that I cannot blame anyone who refuses to go near it. But not only does the Dungeon Crawler Carl series overcome its own absurdity, it’s a giant fantasy mega-series that is somehow getting better as it goes on. And it’s not just me! Damn near everyone I know who has read these books agrees! They start good and they keep getting better. My wife is not a huge fan of fantasy, and she picked up the first book begrudgingly, on my recommendation (much as I picked it up begrudgingly, on the Internet’s recommendation) and she read all seven books back to back. That is not a thing she does!

These books are amazing, and Matt Dinniman is some sort of evil genius, and it is entirely possible that I will read the entire series again before Book 8 comes out, and it would be utterly absurd for me to pick anything else as the best thing I read this year.

HONORABLE MENTION, in NO PARTICULAR ORDER: The Message, by Ta-Nehisi Coates; The God of the Woods, by Liz Moore; Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar; The Bones Beneath My Skin, by TJ Klune; A Drop of Corruption, by Robert Jackson Bennett; Revelator, by Daryl Gregory, It Rhymes with Takei, by George Takei, Harmony Becker & Steven Scott; Advocate, by Daniel M. Ford; The Blighted Stars, by Megan O’Keefe, A Promise of Blood, by Brian McClellan; An African History of Africa, by Zeinab Badawi, Shadows Upon Time, by Christopher Ruocchio, and The Silverblood Promise and The Blackfire Blade, by James Logan.