Testy stuff experts could discuss all of the following in scholarly type terms, and God bless them for that. But let me try to explain in more ordinary English why standardized tests must fail, have failed, will always fail. There’s one simple truth that the masters of test-driven accountability must wrestle with, and yet fail to even acknowledge:

It is not possible to know what is in another person’s head.

We cannot know, with a perfect degree of certainty, what another person knows. Here’s why.

Knowledge is not a block of amber.

First, what we call knowledge is plastic and elastic.

Last night I could not for the life of me come up with the name of a guy I went to school with. This morning I know it.

Forty years ago, I “knew” Spanish (although probably not well enough to converse with a native speaker). Today I can read a bunch, understand a little, speak barely any.

I know more when I am rested, excited and interested. I know less when I am tired, frustrated, angry or bored. This is also more true by a factor of several hundred if we are talking about any one of my various skill sets.

In short, my “knowledge” is not a block of immutable amber sitting in constant and unvarying form just waiting for someone to whip out their tape measure and measure it. Measuring knowledge is a little more like trying to measure a cloud with a t-square.

We aren’t measuring what we’re measuring.

We cannot literally measure what is going on in a student’s head (at least, not yet). We can only measure how well the student completes certain tasks. The trick– and it is a huge, huge, immensely difficult trick– is to design tasks that could only be completed by somebody with the desired piece of knowledge.

A task is as simple as a multiple choice question or an in-depth paper. Same rules apply. I must design a task that could only be completed by somebody who knows the difference between red and blue. Or I must design a task that could only be completed by somebody who actually read and understood all of The Sun Also Rises.

We get this wrong all the time. All. The. Time. We ask a question to check for understanding in class, but we ask it in such a tone of voice that students with a good ear can tell what the answer is supposed to be. We think we have measured knowledge of the concept. We have actually measured the ability to come up with the correct answer for the question.

All we can ever measure, EVER, is how well the student completed the task.

Performance tasks are complicated as hell.

I have been a jazz trombonist my whole adult life. You could say that I “know”many songs– let’s pick “All of Me.” Can we measure how well I know the song by listening to me perform it?

Let’s see. I’m a trombone guy, so I rarely play the melody, though I probably could. But I’m a jazz guy, so I won’t play it straight. And how I play it will depend on a variety of factors. How are the other guys in the band playing tonight? Do I have a good thing going with the drummer tonight, or are our heads in different places? Is the crowd attentive and responsive? Did I have a good day? Am I rested? Have I played this song a lot lately, or not so much? Have I ever played with this band before– do I know their particular arrangement of the song? Is this a more modern group, because I’m a traditional (dixie) jazz player and if you start getting all Miles on me, I’ll be lost. Is my horn in good shape, or is the slide sticking?

I could go on for another fifty questions, but you get the idea. My performance of a relatively simple task that you intended to use to measure my knowledge of “All of Me” is contingent on a zillion other things above and beyond my knowledge of “All of Me.”

And you know what else? Because I’m a half-decent player, if all those other factors are going my way, I’ll be able to make you think I know the song even if I’ve never heard it before in my life.

If you sit there with a note-by-note rubric of how you think I’m supposed to play the song, or a rubric given to you to use, because even though you’re tone-deaf and rhythm-impaired, with rubric in hand you should be able to make an objective assessment– it’s hopeless. Your attempt to read the song library in my head is a miserable failure. You could have found out just as much by flipping a coin. You need to be knowledgeably yourself– you need to know music, the song, the style, in order to make a judgment about whether I know what I’m doing or not.

You can’t slice up a brain.

Recognizing that performance tasks are complicated and bubble tests aren’t, standardized test seemed designed to rule out as many factors as possible.

In PA, we’re big fans of questions that ask students to define a word based on context alone. For these questions, we provide a selection that uses an obscure meaning of an otherwise familiar word, so that we can test students’ context clue skills by making all other sources of knowledge counter-productive.

Standardized tests are loaded with “trick” questions, which I of course am forbidden to reveal, because part of the artificial nature of these tasks is that they must be handled with no preparation and within a short timespan.But here’s a hypothetical that I think comes close.

We’ll show a small child three pictures (since they are taken from the National Bad Test Clip Art directory, there’s yet another hurdle to get over). We show a picture of a house, a tent and a cave. We ask the child which is a picture of a dirt home. But only the picture of the house has a sign that says, “Home Sweet Home” over the door. Want to guess which picture a six-year-old will pick? We’re going to say the child who picked the cave failed to show understanding of the word “dirt.” I’d say the test writers failed to design an assessment that will tell them whether the child knows the meaning of the word “dirt” or not.

Likewise, reading selections for standardized tests are usually chosen from The Grand Collection of Boring Material That No Live Human Being Would Ever Choose To Read. I can only assume that the reasoning here is that we want to see how well students read when they are not engaged at all. If you’re reading something profoundly boring, then only your reading skills are involved, and no factors related to actual human engagement.

These are performance task strategies that require the student to only use one slice of brain while ignoring all other slices, an approach to problem solving that is used nowhere, ever, by actual real human beings.

False Positives, Too

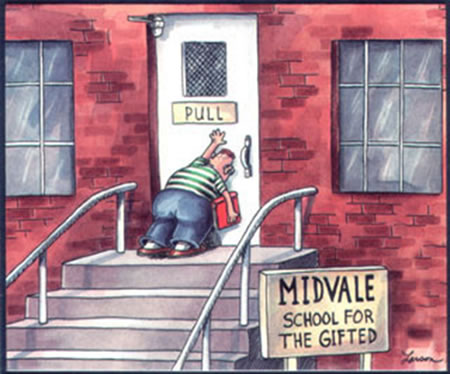

The smartest students learn to game the system, which invariably means figuring out how to complete the task without worrying about what the task pretends to measure. For instance, for many performance tasks for a reading unit, Sparknotes will provide just as much info as the students need. Do you pull worksheets and unit quizzes from the internet? Then your students know the real task at hand is “Find Mr. Bogswaller’s internet source for answer keys.”

Students learn how to read teachers, how to divine expectations, what tricks to expect and how to generally beat the system by providing the answers to the test without possessing the knowledge that the test is supposed to test for.

The Mother of all Measure

Tasks, whether bubble tests or complex papers, may assess for any number of things from students’s cleverness to how well-rested they are. But they almost always test one thing above all others-

Is the student any good at thinking like the person who designed the task?

Our students do Study Island (an internet-based tutorial program) in math classes here. They may or may not learn much math on the island, but they definitely learn to think the same way the program writers think.

When we talk about factors like the colossal cultural bias of the SAT, we’re talking about the fact that the well-off children of college-educated parents have an edge in thinking along the same lines as the well-off college-educated writers of the test.

You can be an idiot, but still be good at following the thoughty paths of People in Charge. You can be enormously knowledgeable and fail miserably at thinking like the person who’s testing you.

And the Father of all Measure

Do I care to bother? When you try to measure me, do I feel even the slightest urge to co-operate?

Standardized tests are a joke

For all these reasons, standardized tests are a waste of everybody’s time. They cannot measure the things they claim to measure any better than tea leaves or rice thrown on the floor.

People in the testing industry have spent so much time convincing themselves that aspects of human intelligence can be measured (and then using their own measurements of measurement to create self-justifying prophecies) that they’ve lost fact of that simple fact:

You cannot know what’s in another person’s head

What goes on in my head is the last boundary I have that you cannot cross. I can lie to you. I can fake it. I can use one skill to substitute for another (like that kid in class who can barely read but remembers every word you say). Or I may not be up to the task for any number of reasons.

Standardized test fans are like people who measure the circumference of a branch from the end of a tree limb and declare they now have an exact picture of the whole forest. There are many questions I want to ask (in a very loud voice that might somewhat resemble screaming) of testmakers, but the most fundamental one is, “How can you possibly imagine that we are learning anything at all useful from the results of this test?”