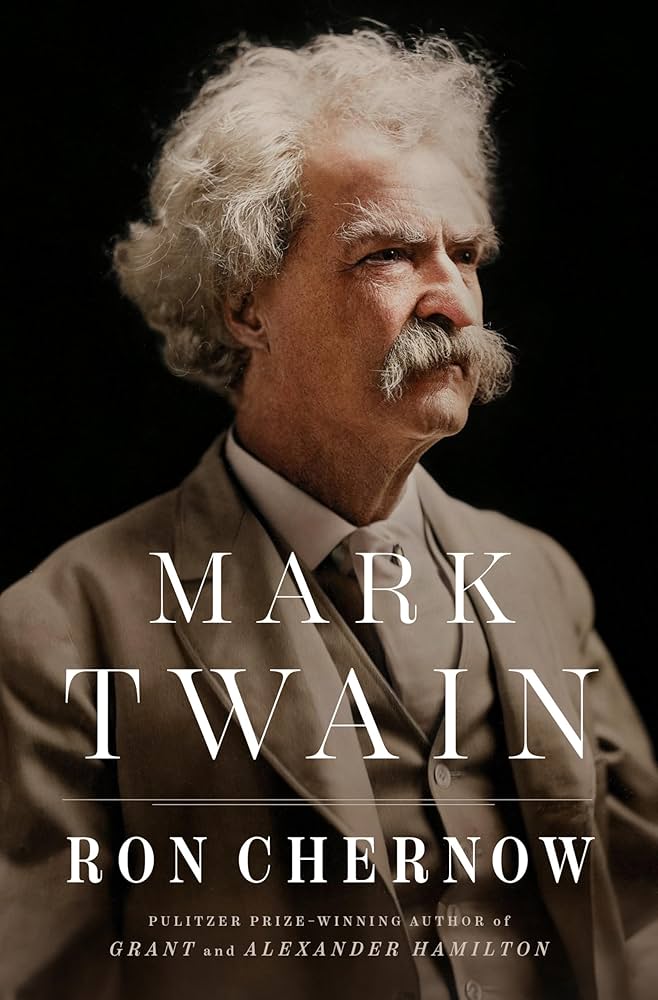

No, no, not a review of Ron Chernow’s book that happens to be called “Mark Twain.” I’m reviewing Mark Twain. And reading Book Mark Twain has caused me to lose a surprising amount of respect for Person Mark Twain. He gets three stars out of five.

Y’all, this dude was weird.

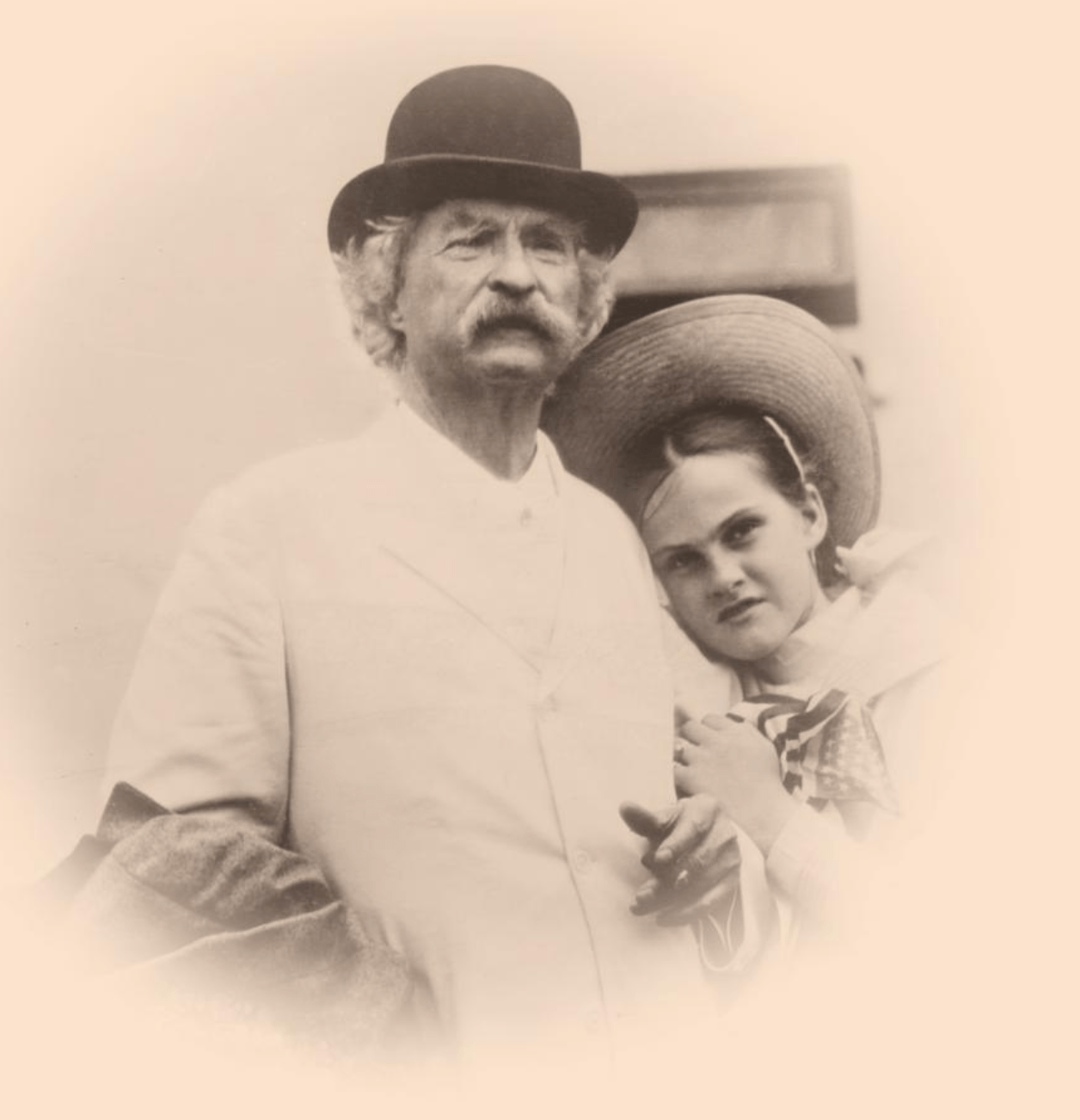

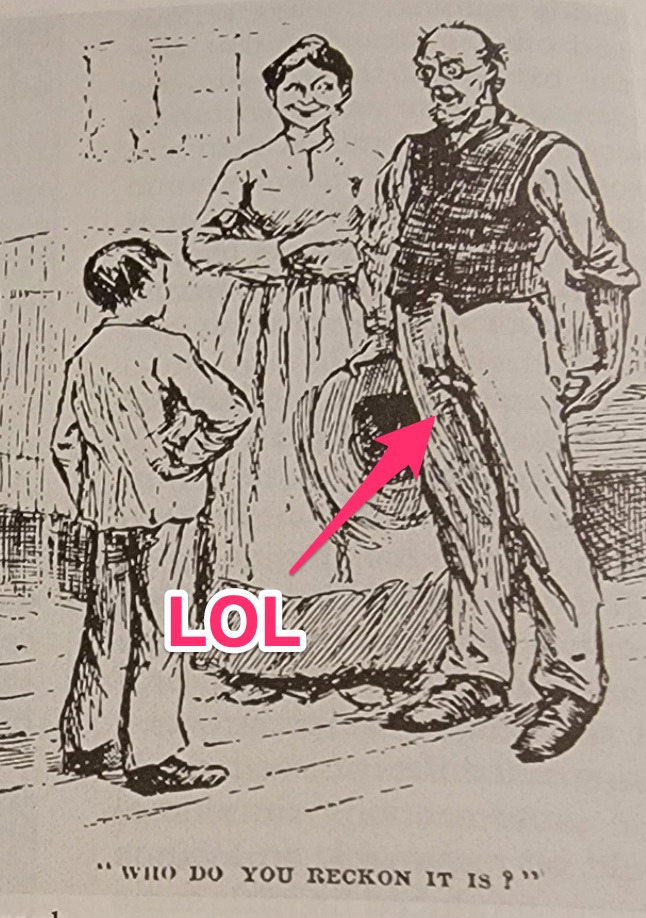

The person Twain is pictured with up there is Dorothy Quick. She is eleven years old in that picture. She and Twain were not related, and they literally met on an ocean voyage in 1907 and Twain, a man in his seventies, just decided to treat her like she was his best friend. They exchanged letters until he died, and he occasionally arranged for her parents to bring her for visits at his home. Multi-day visits.

And she wasn’t the only one. At two different points in his life Twain started a club for girls between ten and sixteen years old, and both times he was the only male member. He called the second group of girls his “angelfish.” They had membership pins. Chernow is quick to point out that there was never any kind of contemporary accusation that Twain’s relationships with these girls were sexual or predatory, but it becomes clear after a while that he recognizes how Goddamn weird the whole thing is and genuinely isn’t sure what to do about it. There’s lots of talk about substitute granddaughters– only one of Twain’s four children survived past her twenties, and his only grandchild was born after he died– but do you really need enough substitute grandchildren to call it a club? And do you stop talking to your substitute grandchildren after they get to be too old for you? Because that happened too. Once his angelfish got into their late teens he lost interest in them. This is not a joke.

Don’t even ask me about Lewis Carroll. Chernow talks about him in a throwaway sentence at one point (literally something like “at least he wasn’t drawing naked pictures of his preadolescent girlfriends, like Carroll was”) and oh my god I hate to talk about falling down a rabbit hole when literally discussing Lewis Carroll, but … yeah.

Twain was terrible at business, prone to falling for outrageous scams, deeply in debt for most of his adult life despite his royalties and his wife being ultra-rich, and held onto a grudge like Kate Winslet on a floating door. There was something vaguely Trumpian about him, where all his friends and business associates were brilliant, salt-of-the-earth, wonderful people until the moment they were no longer useful or Twain felt the need to blame them for something and then they were the worst poltroons and scofflaws in the history of poltroonery and scofflawism.

Like, I’ve read dude’s books. The fact that he was a sarcastic, irascible motherfucker is one of the things I like about him. But I feel like Chernow would have been a lot happier had he just had a chapter called “Look, this guy was a prick,” and gotten everything off of his chest.

There’s nothing genuinely damning in there. I’m never reading anything by any number of authors ever again because of their assorted bastardries and nothing Chernow reveals about Twain rises to that level. Even the angelfish thing is more of a massive ongoing WTF than something that was immoral or should have been illegal. But the last time I came out of a biography or autobiography feeling like I had less respect for its subject than I did going in was Ralph Abernathy’s And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, which I read nine years ago. The only other example I can think of is Jefferson Davis’ memoirs, and I didn’t exactly have warm feelings about that guy going into those books. It doesn’t happen all that often.

Chernow’s book is still a five-star read. Twain still has a ton of five-star books out there for you to read. Twain himself? Three. At best.

…I’m not, really, but I suspect I’m going to get one anyway.

…I’m not, really, but I suspect I’m going to get one anyway.