Super busy tonight, but: if you say to another teacher that you expect 75% of your kids to fail the final that was imposed upon you by the district, and 51% of your kids pass it, is that “good news” or just less bad than you expected?

Tag: standards

Thinking through my grades

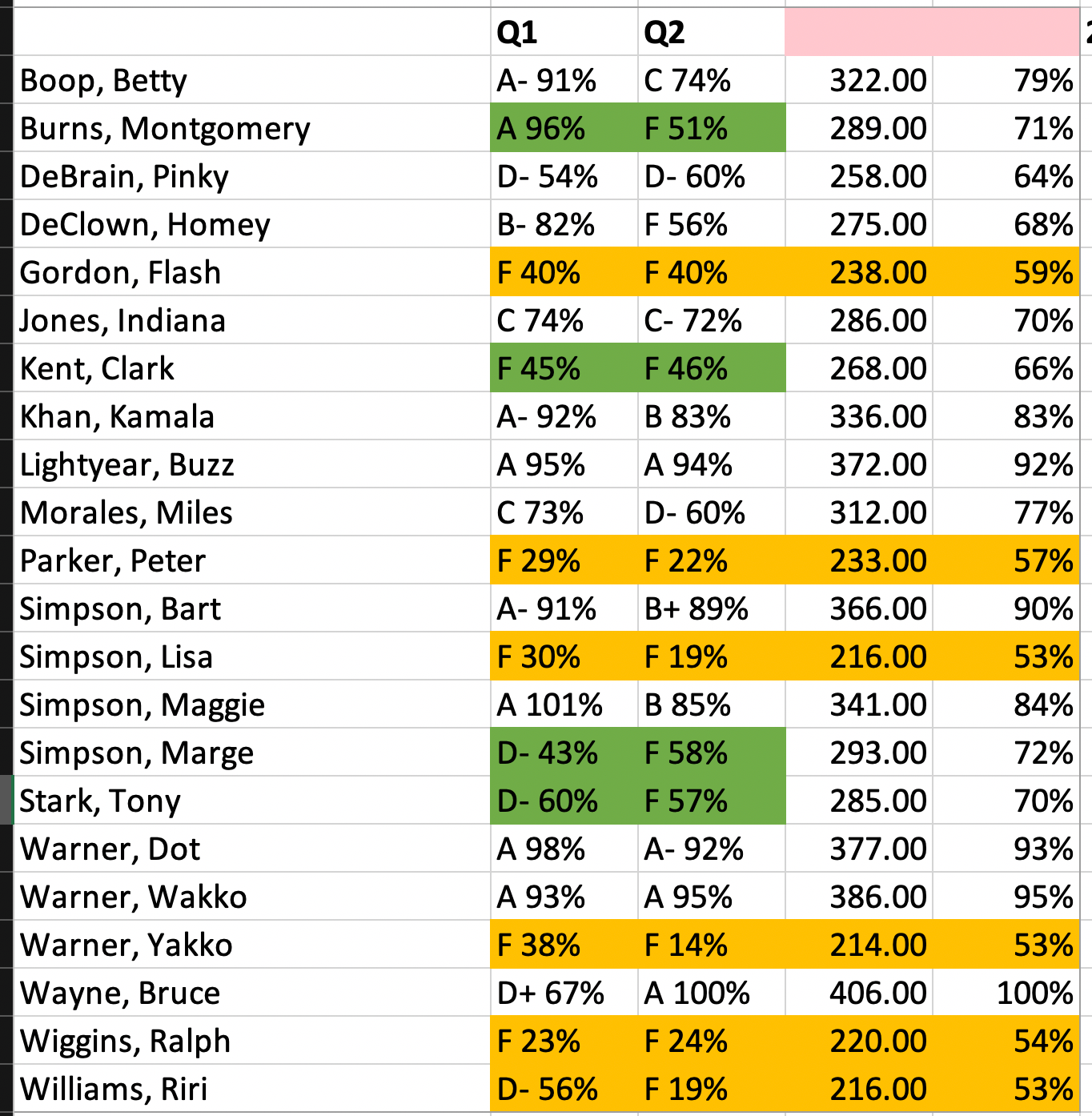

My final grades for the quarter and for the semester are due … well, actually, I don’t have any idea when they’re due, but they’re going to be finished on Friday before noon. I’ve talked before about how much it rubs me wrong to fail any of my kids this quarter, and I’m currently thinking about what I want to do about my grades right now. Represented above are the actual current grades for my first hour students. The Q1 grade is what they actually received (you can see a couple, like Marge Simpson and Riri Williams, whose grades I nudged up a bit already) and the Q2 grade is their current grade with my current policies on grading– ie, nothing turned in and genuinely attempted receives less than a 50%, but work that is not turned in at all receives a 0.

(There are one or two kids whose grades go down slightly; this is an artifact of me doing this quick and sloppy and a couple of extra credit assignments causing weirdness. Ignore those.)

Ignore the third column of numbers, as it’s just their total number of points. The fourth column is their grade in the 2nd quarter if I change every zero to a 50%. The ones highlighted in yellow are the kids who would still fail the quarter under that arrangement. Highlighted in green are the kids whose grades would have been Fs for the 2nd quarter but move into passing range if I bring up zeroes to 50s. Homey DeClown should also be green; I missed him.

A couple of things stand out. First, note Bruce Wayne, who had a D+ during the first quarter and is pulling a hundred percent during the second quarter. Bruce has not suddenly become a good math student, and interestingly, Bruce’s sister’s grade also shot up. I am attributing this to issues at home during the first quarter. Notice also the grade of Montgomery Burns, who was a stellar student first quarter and who fell apart during second– also not, I presume, because all of his math ability suddenly leaked out of his ear.

I have no reason to believe that this class is any different from the rest of mine. We have been given the option of giving an N grade to kids who simply haven’t shown up; N effectively means No Grade. There is talk about high school students having to retake any grade they got an N on and it will not change a GPA. I am fully expecting them to back off on that requirement and I don’t actually know whether it applies to middle school.

At any rate, of the six kids who would still be failing: Flash Gordon has been in touch all year, and I am absolutely certain that the reason he’s not been in school is that he’s been raising his siblings. He’s passing. I should have passed him first quarter, honestly. Peter Parker, as far as I know (and I’m cognizant of the fact that there’s a lot I don’t know) is the kid you’re thinking of when you talk about the kids who don’t deserve the bump they’d get from me fiddling with their grades, because they made their beds and they should sleep in them. Last year he was a smart kid who chose to fail and frankly e-learning hasn’t noticeably changed his grades. The rest of them have more or less been no-shows and would be good candidates for the N grade.

Also, I’m not averaging semester grades. The semester grade is going to be the higher of the two quarter grades, period. I’m doing that even if I don’t end up bumping the zeroes to 50s. The office can fight me on it if they want to; I don’t think they will and frankly it’s a fight that I think I’m well-positioned to win.

A possibly unnecessary explanation

Take a look at this document from the shitgibbon, released before he was elected became President: You will no doubt note all the red Xes, used to designate items that Twitler has not managed to accomplish within his first 100 days. You will also no doubt notice that every single item has a red X over it.

You will no doubt note all the red Xes, used to designate items that Twitler has not managed to accomplish within his first 100 days. You will also no doubt notice that every single item has a red X over it.

Ran into a numbskull on Twitter yesterday who was chastising the person who originally posted the document. “You’re against his entire agenda!” this person said. “Shouldn’t he not passing any of it be a good thing?”

Here’s the thing.

Yes, I’m glad that the shitgibbon hasn’t been able to get much, if any, of his agenda enacted. Yes, I think that’s a good thing. His agenda is mostly completely evil and I don’t want things that are completely evil to happen.

However!

Every so often things happen in America that are supposed to, at least in theory, be beyond partisanship. And, believe it or not, I am generally in favor of competent governance— even when it is run by a Republican. The shitheel in the White House has proven himself throughout his entire life to be absolutely incompetent at every single thing he does. And if and when, God forbid, something happens in this country that demands some sort of nationally unified response, I don’t want morons at the wheel at that time. For all the shit I talked about Mitt Romney while he was running for office, he met the not-especially-high standard of being basically competent and not insane. Hell, I hated George W. Bush with a passion that bordered on deeply unhealthy at times and even that stupid motherfucker could be trusted to occasionally go out in public without stepping on his goddamn dick.

This guy? He’s a 70-year-old narcissist with dementia and a host of raging personality disorders. There is no one in the White House who has ever so much as passed a bill in Congress.

So yeah, I’m perfectly capable of hating his entire agenda and finding fault with his complete inability to pass even the tiniest part of it. Because they mean he’s fucked up in completely different ways, and none of them are any good.

(Also, and somewhat unrelated, I’m frustrated with Republican America’s utter inability to see through this fucker during the campaign. There was never any chance at all that he was going to be a good President. He’s never been good at anything in his life. Never once. That was not going to change once he got the hardest job on the planet.)

On intimidation

And suddenly, now, with just barely over a week left until school starts, I’m stressed out.

And suddenly, now, with just barely over a week left until school starts, I’m stressed out.

The worst teacher I ever had– by such a margin that the title is not even in question– was my freshman honors Algebra teacher. I got a D in his class during the third quarter; I don’t remember the grades in the other three, because the D was so shocking– it was not only the only D I got in my entire academic career, I’m almost certain that there weren’t even any Cs to keep it company.

After every test, he would change the seats. He’d arrange everyone by grade, with no attention paid to any other aspect of seat arrangement– such as, say, whether you could see the board or not. The lower your grade got, the closer you were to the front of the room. The very worst grade in the class was reserved for the front row, right by his desk.

He let you retake tests for a better grade. The retake test would be from a different textbook, though, and if you were retaking Chapter Four’s test, you’d better hope that Chapter Four from that other textbook covered the same material or something you could handle, because if not, too bad– he averaged the two grades together, meaning it was entirely possible to pull your grade down for the retake. Weirdly, most of the kids in his class hadn’t figured out how he was coming up with these new tests; I think most of them just thought either he was really hard or they were stupid. No, he was stupid. And lazy, and destructive.

One of my finer moments in my freshman year– and, honestly, there weren’t many; most of my freshman year memories are painful in some way or another– was figuring his game out halfway through a test retake that I was utterly bombing and, instead of turning the thing in at the end of the hour he’d given us after school, ripping the thing to shreds and throwing it away instead. Minor rebellions, obviously, but it felt good: I figured out your game, John, and you can go fuck yourself.

I hated that fucker. Now, twenty-two or so years later, I’m teaching his class– my honors 8th graders are taking freshman-level Algebra. I have the textbook right in front of me. Now, mind you, I know this shit. I made it through the year and I have repeatedly demonstrated over the course of the intervening years (if nothing else, by passing the PRAXIS; I was in the ninth decile somewhere) that I can handle this material.

But man, am I suddenly sweating teaching it.

Flipping through the book has been intermittently terrifying in the way that flipping through math textbooks is always terrifying; looking over what I’ll be covering in the first six weeks revealed a couple of vocabulary words that I didn’t immediately remember the definitions of but produced an “Oh, that” type of reaction when I found the definitions. Most of it really isn’t so far from the math I’m teaching. But I don’t want to be adequate about this. I want to already be the best Math teacher these kids have ever had, and by the end of taking their second Math class with me I want to be even better.

Terror! Whee!

One other thing that’s hammering on me, here, is the teacher I had for sophomore year math– Geometry, in other words. At the time, he was the best Math teacher I’d ever had, and one of the best teachers, period. Then I had him again for Calculus senior year. And it wasn’t the same. I don’t know what changed, really; if I just had really bad senioritis and I wasn’t prepared to take his class as seriously as it deserved (I was also taking Physics, which was kicking my ass just as hard as Calculus was, but I was excelling in Physics despite the workload) or if he didn’t feel as confident about the material, or if he was trying to Hold Us to a Higher Standard and it just wasn’t working out, or what. But it wasn’t the same. If I’d only had him for Calculus, I’d have forgotten his name by now, and honestly my goodwill toward his class would have worn out a hell of a lot sooner. I only made it as far as I did because I’d liked him so much sophomore year.

These kids loved me when they had me in sixth grade. (Something like 30 of the 33 kids were in my class that year; this isn’t an exaggeration.) Now they’ve got me two years later, for what should be a much harder class. This isn’t exactly a shaky analogy I’m constructing here.

Not only do I have to do better than one of the worst teachers I ever had, at the material he was supposed to teach me, which is intimidating enough, I have to outdo one of the best teachers I ever had, by being better than he was the second time around.

I ain’t saying I’ve bitten off more than I can chew; I don’t think I have. But damn, does my mouth feel full right now.

In which I fix everything (part 3 of 3)

For the last two days I’ve been griping about standardized tests, brought on by this article and Diane Ravitch’s reaction to it. I hope I’ve adequately demonstrated that relying on a pass-no-pass model for determining effectiveness in schools is at least pointless and at most actively destructive. I’ve also talked about the alternative to a pass model, which is a growth model, and offered some criticisms of how growth models, at least as they’re practiced in Indiana, tend to work.

Here, I’ll present an outline of how a growth model for standardized testing ought to work.

- First, and most importantly: remove any notion of “passing” and “failing” completely from the testing process. The two most well-known standardized tests in America right now are the SAT and the ACT, the two tests for college readiness, taken by nearly every high school student at some point or another. Even kids who don’t necessarily plan on going to college take at least one of those two tests, and many take both. Have you ever heard of someone “failing” the SAT? No. Because it can’t be done. You can get a terrible score on it, yes, but you can’t fail. Your score is your score. As it stands right now, creating a cutscore for “pass” and “fail” does the following: 1) It makes the test scores easier to manipulate (just change the cutscore and it looks like more kids passed– or that you’ve demonstrated “higher expectations”) 2) it puts an artificial, pointless barrier between kids who barely passed and kids who barely failed (there is no difference between a kid who got a 450 or a 46o; that’s a question or two. It’s I-had-breakfast-and-eight-hours-of-sleep versus I-sorta-have-a-cold-today. But if you put the pass cutscore at 455, it looks like a huge difference. 3) It embeds a shaming mechanism into the test that has no good reason for being there; 4) It creates an incentive for teachers to focus solely on the “bubble kids;” 5) It provides no useful information to anyone that the actual scores did not already provide. There’s no reason for these tests to have a passing score. It is an entirely useless piece of information. I can think of only one exception, which is when districts use test scores as part (PART!!!) of a decision on whether to pass a student from one grade to another. Most districts don’t do that, though, since frequently scores aren’t available until very late in the year– it’s the second week of July already and I don’t know my kids’ scores yet.

- Removing the notion of pass/fail from the equation makes it easier to focus on growth as the metric. As I’ve demonstrated already, this means that you can’t exclude any of your kids as “unimportant” to your school’s or your classroom’s end-of-year scores. How a student’s score changes from year to year becomes vastly more important than what their score actually is, which is as it should be. There’s a bunch of ways to do this; Indiana’s model has some good points but is unnecessarily complicated. Here’s my suggestion:

- Pick a start year; any start year. Divide those kids into groups based on percentile scores on the test. I like using decile groups (in other words, ten) but you can use quintiles or quartiles or whatever. In Year Two, determine how much those kids moved in their test scores from year one to year two. There are a bunch of ways to quantify this depending on how mathy and technical you want to be about it; the simplest way is to determine movement by thirds. In other words, let’s say the lower third of decile A went from a drop of 140 points to a gain of 10 points, the middle third went from a gain of 11 points to a gain of 90 points, and the top third went from a gain of 91 points to a gain of a million points. You could use standardized deviations from the average or something else if you wanted, but the point is there’s a different standard based on your decile. This means that the kids in the top decile (who don’t have a lot of movement up left for them) can only gain a few points or possibly even lose one or two and still be “high growth,” and kids who start in the low decile and drop anyway would probably be “low growth” kids. This allows some recognition of where the kids started from without looking as random as Indiana’s model does, where a kid who got a 525’s growth model looks wildly different from a kid who got a 526; it should be a bit more predictable as well.

- In Year Three, you determine how much they moved from Year Two, and so on.

- Kids who transfer into a district aren’t a problem because they should have some sort of score from their previous district, and even if they were taking a different test in their previous district a percentile score on that test should be trivial to establish. They then join whatever decile their percentile score belongs to. If they literally took no standardized tests in their previous district because of their age or their district’s policy on standardized tests, well, the world doesn’t end.

- Teachers and schools are evaluated by how many kids they have in the “average growth” and “high growth” categories. Those kids should have been enrolled in the district for a certain minimum number of days (I’d say no less than 75% of the school days up to the test week) and– and this may be controversial– should have been present for a certain minimum number of days as well, and I’d say the absence number should be more stringent than the residence number. I can’t teach a kid who isn’t in school, and I also can’t control whether a kid’s in my classroom or not. Individual districts or states can determine on their own what their requirements for average growth and high growth numbers should be.

One disadvantage of this is that it does make it more difficult to present school data to the public in an easy-to-understand, useful format. One big advantage of the pass rate is that parents understand it; moving from 50% pass to 52% pass has a clear meaning, while we’d have to present averages and medians and all sorts of other data to make the new model understandable when we’re comparing schools. That said, if you want a “one number” comparison, providing the sum of the “high growth” and the “average growth” kids would do nicely; giving all three, combined with averages and medians of actual scores, would provide sufficient information, and anybody who wants to dig deeper (provide numbers per decile, too, maybe) is welcome to.

It’s not great– we’re still paying too much attention to standardized test scores– but it’s certainly better than what we’re doing now. Feel free to comment (Please! Comment!) with suggestions and questions.

Be prepared, by the way, for me to find something utterly irrelevant to gripe about tomorrow.

On “high expectations” (part 2 of 3)

Yesterday I talked about some of the problems that we run into when we try and use standardized test scores as a measure of student, teacher, or school progress. One of the ideas that always comes up when we talk about this is that we should have “high standards” and “high expectations” for our students, and that when we acknowledge that some people aren’t starting the race at the same place as others we’re somehow not properly Standarding and Expecting things of them.

Yesterday I talked about some of the problems that we run into when we try and use standardized test scores as a measure of student, teacher, or school progress. One of the ideas that always comes up when we talk about this is that we should have “high standards” and “high expectations” for our students, and that when we acknowledge that some people aren’t starting the race at the same place as others we’re somehow not properly Standarding and Expecting things of them.

Sounds good, right? High is better than low! Standards and Expecting Things are good, too! So we should definitely have High Standards and High Expectations.

Well, great. Sure.

What’s that mean?

No, really. I’ll wait.

And there’s the problem, see. You aren’t really saying much of anything useful when you say you have High Expectations and High Standards, and you run the risk of saying something incoherent if you’re not careful.

Let’s address high standards first. “Standard” has a pretty specific meaning in the education world. The Common Core is a set of standards; most states still have their own, as the Core isn’t completely phased in yet across much of the country (and is a subject of no small amount of controversy on its own, I should point out). To say that we should have High Standards is basically just saying that we should be teaching kids material that challenges them to some extent or another and (usually) what the speaker actually means is that kids nowadays should be learning either the exact same stuff they learned in that grade or something more complicated.

You can argue the merits of individual sets of standards; I happen to believe that, at least in sixth grade math, Indiana’s standards are pretty solid, and while I have a quibble or two with how the Common Core handles things I don’t have much of an argument with it. Just tell me what to teach; I’ll get the job done. What we don’t have, in any state or jurisdiction or locality that I’m aware of, is any situation where the standards are different for black students or white students or girls or ELL kids or anybody else. Standards are standards; they’re out there and they’re not disaggregated at all.

So what we’re really talking about here is what we expect from our kids.

And for expectations to be meaningful, they have to be specific. You can say that you expect everyone to do well. Great! Also pointless. Heck, you can expect anything you want. I can expect that my students will bring me cookies and milk every day and hurl a virgin sacrifice into the smoking maw of a nearby volcano for me once a month, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to happen.

Lemme say it again: expectations must be specific to specific students in order to be meaningful.

A few examples, all based on real kids I had last year: Velma had the highest math score in the fifth grade before landing in my room. Velma, frankly, doesn’t have a lot of room for growth. She was already pretty close to getting as high a score as scores can get.

I told her she’d gotten the highest score in the fifth grade. She was excited and proud.

“I expect the highest score in the school this year, y’know,” I said. Which, honestly, was asking her for maybe a ten-point bump in her score. In all seriousness, my challenge with Velma last year was to keep her realistic. I haven’t seen her ISTEP score for sixth grade yet, because reasons, but when you start off with a score as high as hers is and there’s an upward limit to how well she can do, the simple fact of the matter is no matter how good a teacher I am her score is likely to drop. Demanding perfection from her would have been stupid. It would have stressed her out and stressing her out would not have helped her performance. I used the “best score in the school” line once or twice over the course of the year, mostly to hassle her, but short of a nosedive there’s not much she could have done to disappoint me with her score. She’s a great kid and I know she did her best.

“Do your best!” sounds like weasel language, doesn’t it? That’s not high expectations! Should I have ridden the kid like a donkey all year about driving her enemies before her and hearing the lamentations of their women to avoid the “lacks high expectations” canard? No, of course not; screw that. Expecting a kid to do his or her best is really all you need to do if you have a kid who actually will do their best, and there was never any risk of Velma giving me less than 100%.

Fred, on the other hand, had the lowest math score in the fifth grade. His math score was seriously a hundred points lower than the second-lowest kid I had. It was so low that I was seriously wondering whether he got off by a number or something and had managed to answer every question on the wrong line.

Early on in the year, Fred’s mother requested a parent/teacher conference with me and asked me flat-out if I thought he was going to pass ISTEP with me as his teacher. And I told her that there was basically no chance whatsoever of that happening. I more or less guaranteed her that her son was going to fail again. He was just too damn far behind; too far to catch him up to grade level in a single year barring a miracle or him moving into my damn house.

And then I told her that I wanted to see a higher point gain from Fred than any other kid I taught this year, and spent about fifteen minutes explaining exactly how we were going to do it, and then worked my ass off all year keeping him as close to on-track as I possibly could. And now, eight or nine months later, there’s maybe one kid out of the fiftysome I had last year whose score I want to see more than I want to see Fred’s. I bet I got a 200 point gain out of the kid– not remotely enough to get him to pass, mind you, but about 166% of the score he got last year.

And now there’s Daphne. Daphne missed passing the ISTEP in fifth grade by something like five points, basically a single question. I looked her mother in the eye on Open House night, which is before school even starts, and guaranteed her that her kid was going to pass ISTEP this year. Dumb? Yeah, probably, but I was in a grand mood. Daphne spent the year ricocheting from one emotional crisis to another; I caught her cutting herself on two separate occasions (note that I’m the one doing this, not her parents,) rarely turning any work in, etcetera. Daphne had a terrible year– but a terrible year that had basically nothing to do with her math class or her math teacher. Do I expect Daphne to have made strides in my math class when Daphne probably did well by keeping herself out of a mental hospital over the course of the year? Of course not. I’d like to see that she made some improvement and, honestly, I suspect she did– she didn’t turn in any work, which meant she spent most of the year failing all of my classes (and that’s a discussion for another time) but she seemed pretty on the ball whenever I was assessing her on anything other than turned-in assignments. But her ISTEP score? I really don’t care anymore. Staying the same is just fine.

You tell me: which kid do I have higher expectations for? Which kid is going to make me look better when and if our test scores get reported solely on pass rates? And, again, notice: for Fred and Velma, the answer is neither. One kid failed and will fail again; one kid passed and will pass again. Neither of them is going to move my numbers at all if we’re using a pass-rate-only evaluation of our test scores. Daphne is a perfect example of a bubble kid (and, I can’t make this clearer: all three of these kids are real) and so my skills as a teacher and my building’s probation status are going to depend on whether one kid who takes one test on one day spent the night before using erasers to scar her own arms or not.

This is unacceptable.

The pass model fails because it does not encourage high expectations. It encourages a narrow focus on a narrow band of kids who can be motivated, bribed, pushed or dragged across that line. And if the state doesn’t particularly like their pass numbers from a test, all they have to do is manipulate the cutscore and– voila!– we had more kids pass than we did last year! We’re Doing Things over here! I am certain that Illinois did this while I am teaching there; I had kids pass the ISAT my second year in Chicago who had absolutely no business “passing” anything at all, and the state and CPS crowed and crowed about our pass numbers. They manipulated the test scores; while I’m not going to go so far as to claim that I didn’t teach my own kids anything, what they did learn from me had precious little to do with their test scores at the end of the year.

I hoped that one of my kids didn’t fall by too much, that one kid failed, and that a third kid just didn’t crater. And I maintain that all three of those things represent “high expectations.”

Any chance of me convincing anyone of that without 1658 words of explanations?

Tomorrow: A method that I think might actually work.

In which this isn’t quite what it looks like (part 1 of 3)

What the hell, let’s get in trouble.

What the hell, let’s get in trouble.

Go take a look at this article first, and then Diane Ravitch’s reaction to the article.

What, you didn’t read? Okay, I’ll summarize. Alabama thinks this is OK and Diane’s mad; the slightly ungrammatical intro is a quote:

- These are the percentages of third-graders expected to pass math in their subgroups for 2013 are:

- – 93.6 percent of Asian/Pacific Islander students.

- – 91.5 percent of white students.

- – 90.3 percent of American Indian students.

- – 89.4 percent of multiracial students.

- – 85.5 percent of Hispanic students.

- – 82.6 percent of students in poverty.

- – 79.6 percent of English language-learner students.

- – 79 percent of black students.

- – 61.7 percent of special needs students.

I can hear your brain, you know. “What?” you’re thinking. “That’s terrible! How dare they set lower standards for everybody other than Asians and whites! That’s racist!”

She’s hollering and yelling about it and so is everybody in her comments (most of ’em, anyway) and I barely had the strength to wade through a third of the comments on the original article.

Let that idea simmer a little bit; I’m sympathetic, believe me. I’m gonna change the subject for a bit but I’ll get back around to this.

Let’s assume that, as we do at the moment, you believe that standardized tests of some kind are a good way to assess student learning. For the moment, I’m not going to debate whether that’s actually true or not; let’s just mutually decide that we think they do. It’s good enough. If you care about standardized test scores, there’s a couple of different ways to pay attention to how schools/classrooms/teachers/kids/whatever do on them. The first, which is the method No Child Left Behind followed for a decade or so, is the raw pass rate, and I think the pass rate is the number that most people are accustomed to wanting to look at. You just calculate how many kids passed out of how many kids took the test, and you’re done. One number, easy to compare to other numbers. It’s great!

If you tell a school, or a district, or whatever, that they’re going to be judged solely on how many kids manage to pass Test X, here is what’s going to happen: the “bubble kids” suddenly become the most important students in the building. Billy, over there, has parents who made sure he was reading before he entered preschool. His house has thousands of books in it, his parents both have graduate degrees, and he had the highest test score in your school last year.

You are not going to pay any attention to Billy. Billy’s going to pass unless you blind him before he takes the test.

Shirley, on the other hand, is the product of a single-parent home and has an array of learning disabilities. The only book in her house is the Bible, and no one in the house can read it. Her mother has been unemployed for eight months and did not graduate high school. Shirley currently lives with her mother, her aunt, and the six other children they have between them and their home situation is at best wildly unstable. She struggles mightily with material four or five grade levels below her age.

Screw Shirley, too. It doesn’t matter how much effort you put into her; she’s not gonna pass no matter what you do unless you take the test for her.

The kid you’re looking at is William. William’s pretty bright, usually, but how well he does depends on his mood. If he’s paying attention, and if he’s taken his meds, he can be a good student. He struggles, and needs additional help, but he generally isn’t the type to just give up on you; he’s a hard worker if he thinks you like him. He didn’t pass last year, but he was close.

Your Williams are now the most important kids in your classroom. Those kids– and they can be a large chunk of your room depending on what kind of school you teach at– are going to determine whether you pass or fail, or whether your school stays afloat or goes on probation. You’re going to spend the lion’s share of your energy on the kids who have a chance to pass the test but aren’t guaranteed to pass the test. The rest of them are what they are; one way or another, it’s a waste of energy.

Sad but true fact: Billy is more likely (but not guaranteed) to be white or Asian, and Shirley is more likely (but again, not guaranteed) to be black or Hispanic. William is a little more blended but he’s a bit more likely to be some shade of brown than otherwise. The so-called “achievement gap” is so pervasive in American schools that I’m not going to waste the breath on talking about it beyond this sentence. It exists. It sucks that it’s real, but it is.

If you focus on pass-only as your measurement method, you’re going to get schools and teachers who focus solely on the middle rather than the top or the bottom. Kids who can’t be moved from fail to pass, or who won’t move from pass to fail, are a poor use of effort. You’ve got to get each and every one of those bubble kids because we have to show “improvement” on our grade’s numbers from last year, even though these aren’t the same kids we were measuring last year, they just happen to be the same age as those kids were.

This, obviously (I hope) makes no goddamn sense at all.

Here’s a better way: pay little or no attention to pass rates, and instead focus on improvement. Okay, it’s nice that Billy passed. Did he do better this year than he did last year? By how much? If the answer is “yes,” you’re doing a good job. If the answer is “no,” there’s a problem. If you have a bunch of Billys and they all did worse than they did last year, you have a real problem.

Shirley? We’re not so worried about whether Shirley passes right now. Shirley entered sixth grade reading at a first-grade level. If you moved Shirley up to third grade in a single school year, you did a good job. Same as William– his score was 40 points higher than he did last year, but the pass cutscore moved up by 45 points. He still didn’t pass, but he did better than he did last year. He showed improvement. This is a good thing.

It is also hideously complicated, and that hideous complication is why we tend to focus on pass rates instead, even though focusing on pass rates is stupid. Pass rates aren’t complicated and they aren’t hard to explain. Indiana, in particular, uses the improvement method, technically called a “growth model.” Every kid that takes the ISTEP is compared to every other kid who got the same score they got last year, and then they’re ranked as either a High Growth, Average Growth, or Low Growth kid. The problem is that sometimes you’ll get some random-ass score that not many people got and a “high growth” score is a point. Or– and I saw this happen– some kids will lose points and still be High Growth, and other kids will gain immense amounts of points but because everyone who got a 512 last year ate their Wheaties before the test this year, that will somehow count as Low or Average growth.

It’s still better. Indiana’s model has stupidities embedded in it– those kids I talk about in the last paragraph are not hypothetical– but it’s still better than relying on pass rates, because every kid’s scores count. I don’t want to just focus on my bubble kids. I want to focus on everybody, because Shirley having a bad year hurts me just as much as William or Billy. When we get down to the nitty-gritty details of who’s High Growth and who’s Low Growth I might find some places to quibble, but as an educator I can’t afford to prioritize one group of students over another.

And that’s a good thing. We want that.

Back to NCLB for a minute. One of the bigger pains in the ass of NCLB was the way it disaggregated groups of kids into subgroups. Not only did your school have to pass a certain percentage of its kids to stay in good standing, but a certain percentage of your black kids and a certain percentage of your ELL kids and a certain percentage of your special ed kids and a certain percentage of your girls and a certain percentage of your blah blah blah blah blah all had to meet Adequate Yearly Progress goals. If just one of your subgroups– and these damn things could be on the level of a single family in a smaller school– was out of compliance, the whole school was. God help you if you had a diverse student body. Somebody was bound to mess up; you were screwed. It made being in a basically segregated school a good thing. If everybody was black (and my school in Chicago was) then you didn’t have to worry about eight different racial subpopulations screwing your numbers up because the Garcias or the Nguyens just got here last year and their kids don’t speak English well enough to pass the test yet. Or because your school has a reputation for having a great special ed department, so you have lots of special ed students because parents fight to get their kids in your school– which means when that large group of special ed students don’t make AYP, your whole building is labeled “failing” because of the very thing that made your building successful.

It sucked, mightily.

What we’re seeing, up there, in that looks-really-racist chart, is a combination of a growth method and NCLB’s disaggregated student populations. They’re acknowledging that the achievement gap exists. We cannot simply state that we want 80% of everybody to pass (to pick a number at random) because it’s unrealistic for all of our groups of kids. Instead, what we want to see is for everyone to make improvement. Well, to improve, our Asian kids have to hit a 93.6% pass rate. Our black kids aren’t passing at the rates that the Asian kids are. We still want improvement from them, but for that group, a 79% pass rate represents improvement. We’re still trying to bring up all of our kids; we’re just realistic about how much we might be able to bring them up from year to year.

Of course, when you present it that way, without– at the moment– 1764 words that no one will read of explanation first, you look racist as hell. And it was a terrible mistake for the state of Alabama to release these numbers like this. But it was a political mistake, not a pedagogical one.

Tomorrow– because this is already too long– I’m going to talk about what it actually means to have “high standards” and “high expectations” and how it works with this type of model.

Unless, of course, I come up with something more interesting.