And. We. Are. Back.

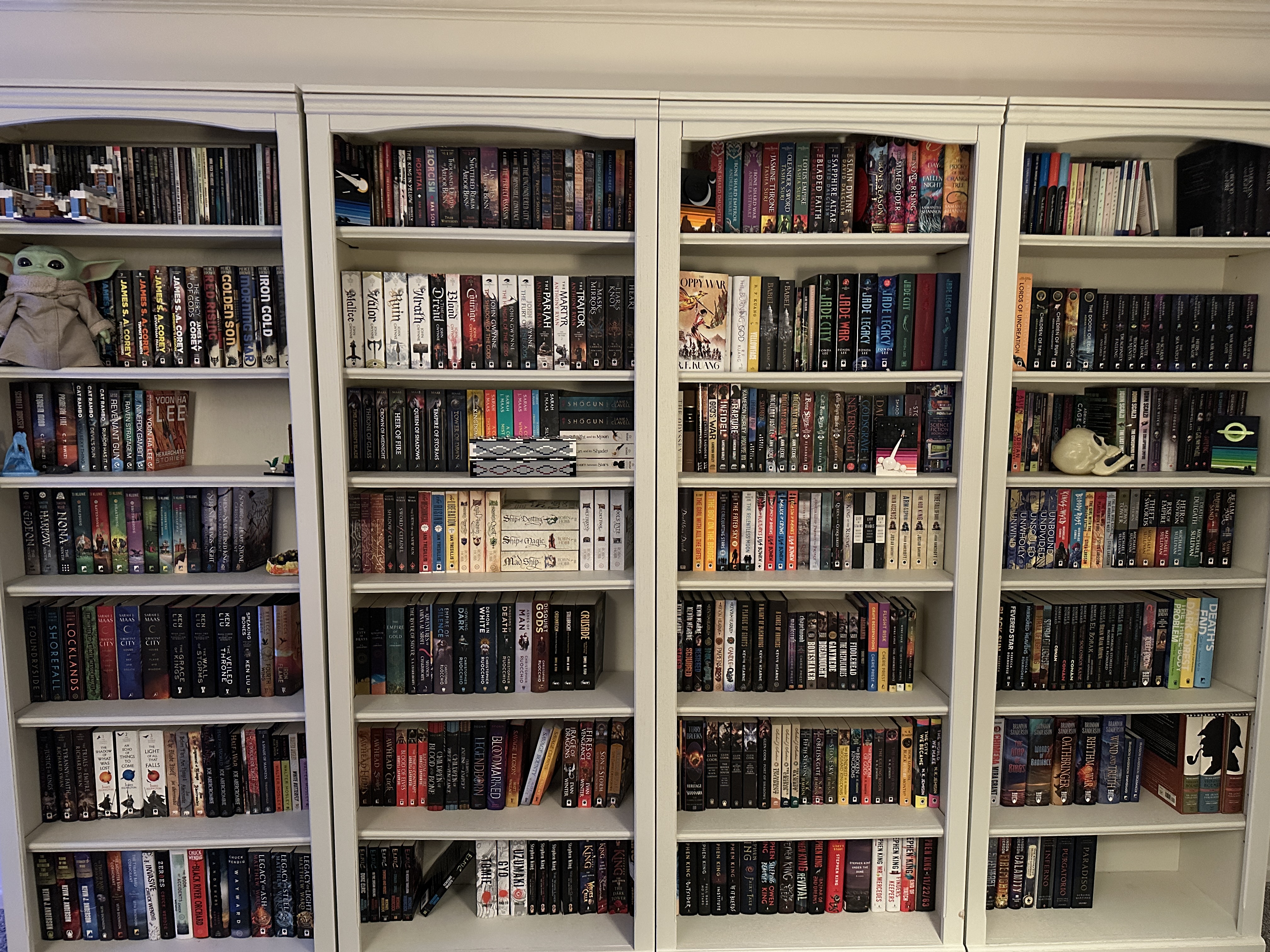

This is the twelfth post in this series that I have written; I spent some time thinking about doing a Best of the Best list and when I realized how many rereads that would require– believe it or not, when you read 100+ books a year it tends to hurt your recall a little bit, like, I’ve literally read well over a thousand books since writing the 2013 list– I abandoned the idea. I am back to 15 books this year because right now I’m at 181 books read for the year and since it is only the 29th I may very well be at 184 by New Year’s Eve; hopefully I don’t read anything too brilliant in the next couple of days because it’s gonna have to wait until next year.

As always, don’t take specific rankings all too seriously– this started as a shortlist of 31, then got cut down to 17, and going from 17 to 15 was really hard, and honestly anything in the top seven or so could have ended up at number one if I’d woken up in a different mood. Also, the asterisk up there means that these books were new to me in 2024; the oldest book on the list is from 1975. I’m pretty sure a majority of them are 2024 releases but it’s definitely not all of them.

Previous lists:

- The Top 11 New(*) Books I Read in 2023

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2022

- The Top 15 New(*) Books I Read in 2021

- The Top 15 New(*) Books I Read in 2020

- The Top 15 New(*) Books I Read in 2019

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2018

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2017

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2016

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2015

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2014

- The Top 10 New(*) Books I Read in 2013

And we’re off!

15: Math in Drag, by Kyne Santos. One of my reading goals for 2025 is to read six books about math and/or teaching math, right? And one of the reasons it’s only six books is that books about teaching and books about math tend to be dry as hell, and despite wanting to improve my craft as a math teacher I like to enjoy what I’m reading.

Kyne Santos needs to write a lot more books about math, is what I’m saying here. Drag queens who post mostly about mathematics is somehow a subgenre on social media, and Santos is the most visible of the group (if you’re on TikTok, check out Carrie the One) and this book is a whole bunch of things at once– a memoir, a history of math, a math textbook, and a history of the drag movement– and it’s tremendous on all levels. I actually took one of the chapters about negative square roots and turned it into a warm-up activity for my 8th graders, and then ensured that they would all look up the book on their own by telling them that I could give them the author’s name but not the actual name of the book. Which, for the record, probably wasn’t true, but I teach in Indiana.

14. How to Say Babylon, by Safiya Sinclair. It’s at this point where I realize there’s more nonfiction or at least nonfiction-adjacent (you’ll see) books on this list than usual, as Sinclair’s book is also a memoir about growing up in Jamaica in the eighties and nineties. Her father was a hard-core Rastafarian and a reggae musician, and growing up smart and female in a very patriarchal religious structure is a big part of the book.

The other fascinating thing about this one is the language; the dialogue is mostly in Jamaican English, which isn’t quite far enough from American English to qualify as a patois (which is a whole other thing, to my understanding) but it means that things like pronouns aren’t going to work quite like you’re used to, and you are going to hear every word her father says whether you normally hear dialogue or not. Sinclair is an award-winning poet, and while I’m not likely to check out her poetry, if she writes any more prose works in the future I’ll be in line for them.

13. Shōgun, by James Clavell. I have never seen either of the miniseries that were based on this book, either the original one from the 1980s or the apparently far superior one Hulu did this year, but I swear that if I ever start watching television again, I’m gonna, dammit. I picked this up (for the record, it’s printed in two volumes because it’s 1500 pages long, but it’s one book) based on a bunch of people being very enthusiastic about the miniseries and the strength of the cover.

Okay, that’s a lie, I picked this up because of the precise shade of blue-green used on the new covers, which sounds ridiculous and I don’t care, it’s true. Luckily for me the book is really good, and a lot less racist than you might guess “book written in the 1970s by a white guy about Japan” might be. The main character, a navigator named Blackthorne, is just open-minded enough of a character to make it possible to get into his head, and the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century were a fascinating period of history both in Japan specifically and the world in general. This book is a heavy damn lift in more ways than one, but I really enjoyed it and I’m glad they didn’t reprint it with a boring cover.

12. King: A Life, by Jonathan Eig. The Civil Rights movement is my favorite period of American history, and easily the one I know the most about, so you can probably imagine that I have a bunch of books specifically about Martin Luther King, Jr. on my shelf, as well as a couple that aren’t officially about him but may as well be. What sets Eig’s version of his life apart from the rest is his focus on King as a human being and not as a man whose face would eventually be carved into marble as a national memorial. It isn’t quite a psychological biography, if that’s even a real thing, but it may not surprise you to learn that King struggled with depression and anxiety for his entire life as well as a healthy dose of imposter syndrome (the man was in his twenties during the Montgomery bus boycott, and was only 39 when he was murdered) and he doesn’t come out and say it, but it’s strongly suggested that his mental health struggles led to his well-known issues with adultery, drugs and alcohol.

What, you didn’t know Martin Luther King dabbled in drugs? Yeah. Sorry about that. But unlike, say, Ralph Abernathy’s book, there’s no sense of score-settling in King: A Life; Eig talks about these things because they were important, and he’s not trying to knock King off his pillar so much as talk about a guy who would have been deeply uncomfortable up there in the first place. When you’ve read as much about King as I have it takes a lot to write something new and impressive, and Eig has certainly delivered here.

11. Seal of the Worm, by Adrian Tchaikovsky. This is the first of two books on this list that should be understood as endorsements of the entire series rather than the individual books I’m writing about, and in the case of Seal of the Worm I’m talking about his Shadows of the Apt books, a ten-book, 6000-page series, most of which I read in 2024.

That isn’t to say that Seal of the Worm isn’t the best book of the series, as even just from a technical level capping off that massive of a work in a satisfactory manner is an impressive achievement all on its own, but what if I told you that Seal of the Worm manages to introduce an entire new antagonist and kicks the legs out from underneath all nine previous books, something that has already happened once in the series? Tchaikovsky may be science fiction and fantasy’s most underrated author, and I still don’t know anyone else who has read this series, which is a Goddamned crime. They’re right there, and you can buy them. What are you waiting for, other than the time to read six thousand pages? Please, somebody, read this.

10. Light from Uncommon Stars, by Ryka Aoki. Another mini-theme of this list that is going to start becoming more apparent is books that are batshit nuts, and … man, this book has a little bit of everything in it, and I think would wear a “batshit nuts” badge with absolute and undeniable pride.

I mean, check out how many whole entire books are superglued together here: Light from Uncommon Stars features 1) a young, transgender runaway who is 2) a world-class violinist who 3) meets a mentor who has made a deal with the Devil to 4) corrupt seven young violinists into also selling their souls to the devil and 5) is looking for number 7, and meanwhile 8) there are aliens who 9) are stuck on Earth and 10) running a donut shop while they’re stuck here. It is complete madness from the first page to the last, and I recommended it to one of my trans orchestra students during the last school year and I should really find out if they ever read it or not. Meanwhile, you should read it too.

9. The Phoenix Keeper, by S. A. MacLean. Slightly less nutty (but still pretty nutty) is this book about an autistic, anxiety-riddled zookeeper in a zoo filled with fantasy animals, the first and sole representative of what the kids are calling cozy fantasy on this list. I got sent this one by Illumicrate and it wouldn’t have really crossed my radar otherwise, but I read it more or less cover-to-cover during a car trip and it was exactly the book I needed at the time. I have read more romance books than I ever expected to this year, and am reaching the point where I am heartily tired of romantasy, which is a thing, but this isn’t that; there is a bit of a romance subplot but it’s not about that, so don’t pay attention to the blurb on the cover. No, this book is about a nerd who really really wants to be the best zookeeper in the world and wants to raise phoenixes, and it’s really obviously based on the efforts zoos went to to keep the California condor from going extinct, and I absolutely loved it. There are setbacks and obstacles to be overcome but, again, this is cozy fantasy and you know everything is going to work out just fine, and this book is more about relaxing into the details and the characters than the conflict. I like zoos. I like books set at zoos. Zoos with phoenixes are better than regular zoos. This is a great book.

8. Tupac Shakur: The Authorized Biography, by Staci Robinson. I am tempted to say “this exists and therefore you should read it,” but that’s kind of unfair to both the book and the author even if it’s more or less completely true. I’m listening to Kendrick Lamar while I write this post, and Kendrick is one of Pac’s more obvious spiritual successors in hiphop nowadays, but it’s impossible to overstate the impact this guy had on rap music and on two or three generations of kids and still counting. I think it’s probably fair to say that there’s not another musician from the nineties (or a whole bunch of other decades, for whatever that’s worth) that still has as much influence as Tupac does, and reading a book written by someone who knew him well and was handpicked by his mother to write the book was an absolute pleasure. The guy’s life was fascinating, and while books about musicians can sometimes become formulaic (“he released this, and then he released this, and then there were the drug problems, and then he released this,”) this manages to keep away from that. The one weakness is that it literally ends with the moment of his death; I feel like another chapter about the LAPD’s investigation reaction to his murder was probably warranted and we didn’t get it. Still, I’m glad to have read this.

7. The West Passage, by Jared Pechaček. I still don’t know how the hell to pronounce his last name, but this book is the first one on the list that, on a different day, I easily could have called the best book of the year, and if you want to draw a line between the first eight books and the last seven and ignore the ratings completely after that, it’s entirely reasonable. The West Passage is also the second representative of the Batshit Nuts genre, drawing inspiration from Gormenghast and Shadow of the Torturer and Through the Looking-Glass and China Miéville’s Bas-Lag series and coming up with something where characters will be talking about a beehive, and you’ll think to yourself okay, I know what bees are, and I know what a beehive is, and then the beehive will walk over to the characters on its legs and extend a urethra and piss out some honey for them. The crumbling castle this book is set in is one of the wildest settings I’ve ever encountered in fantasy literature, and God damn it did I seriously read six more books this year that I thought were better than this one? That shouldn’t be possible, because this book is incredible, but … well, keep reading.

6. Mornings in Jenin, by Susan Abulhawa. I read several books this year by Palestinian authors, and two specifically by Abulhawa, whose Against the Loveless World was also on my shortlist, but Mornings in Jenin is the superior of those two books. This is not a memoir but feels like it (Abulhawa herself is Palestinian, but was born in 1970 in Kuwait, so she’s narrating events from before she was born, although I’m sure her own life experiences made their way into the book), and it begins with the creation of Israel and runs up to more or less the modern day, as it ends in 2002 or so, a few years before its release in 2006. This is easily the most important book on the list, and the main character, Amal, is a young girl at the beginning of the book and an old woman at the end of it, so you more or less get the entire history of the Palestine-Israeli conflict through her eyes. Go right ahead and make a list of all the content warnings you can think of, as this is a really hard book to read if you’re possessed of even a modicum of human empathy, but it’s something that I think most people and certainly most Americans definitely need to pick up.

5. Incidents Around the House, by Josh Malerman. I called this the scariest book I’d ever read when I wrote about it the first time (my post cannot, in any meaningful way, be called a “review”) and while I wasn’t able to stick by that– you’ll see in a minute, and frankly parts of Mornings in Jenin are horrifying in their own way as well– it’s certainly the scariest horror novel I have read, at least in a long, long time, time having worn the edges off of some of the other books that might belong on that list.

Incidents is about Bela, an eight-year-old, who lives with her mother and father in a nice, comfortable house. But there’s also Other Mommy, who no one else in the house can see, and who asks Bela every day if she can “go inside her heart.” Bela is smart enough to realize that this is probably a Bad Idea, possibly one of the Badder Ideas in the entire history of Bad Ideas, and … well, Other Mommy isn’t very happy about that.

Don’t read this book. You don’t need it in your head. I didn’t need it in mine, but it’s there now, and the book is still in the freezer, and I have to reward how fucking effective this book is in scaring the absolute shit out of a grown man who himself lives in a nice comfortable house even if I am never letting it out of the freezer ever again.

4. The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi, by Shannon Chakraborty. I haven’t used the word delightful in this post yet because I feel like I overuse it lately, but I feel like there’s probably no way of getting through writing about this book, about a female ex-pirate captain who has retired and settled down to raise her daughter in a magical world full of djinn and treasures and adventures and her pain in the ass mom and awesome, but this was probably the most fun I had reading anything this year, and if you can look at that cover and not immediately want to read this than you and I probably can’t be friends. I’ve read several of Shannon Chakraborty’s books, and this is better than anything she’s written before– and those were all books I enjoyed! I want twelve thousand more books about Amina al-Sirafi and I want them right now. Have you ever noticed that when I get excited about things my sentences tend to get longer? Look at the first sentence of this entry. I read this book months ago. It still makes me that happy to talk about it. Go read it.

3. Blood over Bright Haven, by M.L. Wang. This is the fourth book in a row where you’re going to feel a particular emotion over and over again while reading it, and the second of the four where rage is going to be that emotion. Blood over Bright Haven has a bunch of very interesting tricks under its sleeve, and chief among them is the way it’s going to kind of blindside you partway through with what it is actually about and, even more amazingly, who its main character is. This is one of the angriest books I’ve ever read, and again, one of the books I just finished writing about is about a Palestinian refugee, so that’s a pretty high bar. I enjoyed Wang’s Sword of Kaigen but not nearly as much as I expected to, and this book sat on my shelf for a while before I got to it. It should be this book that people can’t stop talking about, not Kaigen, and the reason I’m not talking about the plot very much is that this is definitely one of those books where you need to go in knowing as little as possible. Just sit back and let it take you for a ride. And if you can, grab it soon while you can still get the cool red-stained edges. The first hardcover edition is sweet.

2. Nuclear War: A Scenario, by Annie Jacobsen. Remember a couple of books ago, where I called Incidents Around the House the scariest horror novel I’d ever read, and said that I’d explain in a minute? Yeah, that’s because Nuclear War: A Scenario isn’t a novel, and it is fucking terrifying on a deep, existential level that no fictional novel can really touch.

If you grew up in the eighties, you remember what living in fear every day of impending nuclear war felt like, and you might remember the occasional “hide under your desk and kiss your ass goodbye, because it’s not going to help” drill from school. Jacobsen’s book starts with North Korea detonating a one-megaton nuclear bomb over Washington DC, and ends seventy-one minutes later with more or less all of human life on Earth extinguished. It is probably best classified as near-future science fiction, as the events described have not, in fact, happened yet, but Jacobsen is repeatedly clear that the events of the book could happen tomorrow, and while there’s clearly some fictionalization happening here and there (she has to invent a US President and Vice-President, for example, and what happens with the president pro tempore of the Senate almost verges on comedy) I have shelved this with my nonfiction and history books, because all of the research that went into this puts it more firmly into the realm of those books than fiction.

I, uh, want to die in the first thirty seconds, preferably entirely unaware of what just killed me, if there’s a nuclear war. I’ve said this before about more fictional apocalypses– I also want to be patient zero if there’s ever a zombie outbreak– but it would be great if I was, say, in Chicago when the bombs hit, and if that first exchange involved more than the one bomb. I’d prefer not to die in a nuclear apocalypse, mind you, but if I’ve got to go that way, I really don’t want to see it coming.

1. Godsgrave, by Jay Kristoff, is my favorite book of the year, and my annual irritation with WordPress that it will not allow me to begin a paragraph with a one and a period without indenting it automatically or Performing Shenanigans to keep it from happening. I am capable of indenting things myself if I want to, or you should at least pay attention if you automatically indent something and I delete it, dammit! But yes: this is the second single-book-as-a-stand-in-for-an-entire-series, and Kristoff’s Nevernight Chronicles is one of the most amazing series I’ve ever read. In broad strokes, the series feels like something you’ve read repeatedly– a young girl who trains to be an assassin so she can seek revenge is not on the top 10 of most original scenarios– but once you get past that original setup and the series gets moving, you’re going to be surprised over and over and over and over by the story decisions Kristoff makes, and the reason I picked Godsgrave, the second book in the series (the first and last are Nevernight and Darkdawn, respectively) is that it ends on a cliffhanger so potent that I literally screamed when I finished the book, and if I had had to wait for Book Three to come out and hadn’t had it sitting on the shelf waiting for me (I read all three books in a single gulp) I might have had to move into his Goddamned house until he finished it.

I love so many things about this series. I love what an unapologetic asshole Mia Corvere is. I love that they make her an assassin and then don’t back away from all the killing that implies. I love that Kristoff sets up what feels like a bog-standard YA love triangle and then blows it to hell. I love how much of the worldbuilding is stuck into what feels like inappropriately snarky footnotes, and I love how the footnotes suddenly make sense at the end of the book. I love how meta the series gets, and I love how no one is safe, ever, and how Darkdawn keeps you on your toes for its entire length and keeps getting more and more batshit, at one point indicating a story development with margin changes, and God Damn I want to sit down and reread this whole series before starting the Stormlight reread in a few days.

The Nevernight Chronicles is the best series I read this year, and Godsgrave is the best book of The Nevernight Chronicles. Go forth.

Honorable Mention, in No Particular Order: A Mystery of Mysteries: The Death and Life of Edgar Allan Poe, by Mark Dawidziak; The Honey Witch, by Sydney J. Shields; House of Hunger, by Alexis Henderson; The God and the Gumiho, by Sophie Kim; This is Why They Hate Us, by Aaron Acevedo; The Bone Ship Trilogy by R. J. Barker; Somewhere Beyond the Sea, by T.J. Klune; Blood at the Root, by LaDarrion Williams; The Vagrant Gods series, by David Dalglish; Morning Star, by Pierce Brown; Bookshops & Bonedust, by Travis Baldree, Moon of the Turning Leaves, by Waubgeshig Rice, and The Fury of the Gods, by John Gwynne.