Wow, that’s bigger than I thought it was going to be.

Oh well. Scrolling’s free.

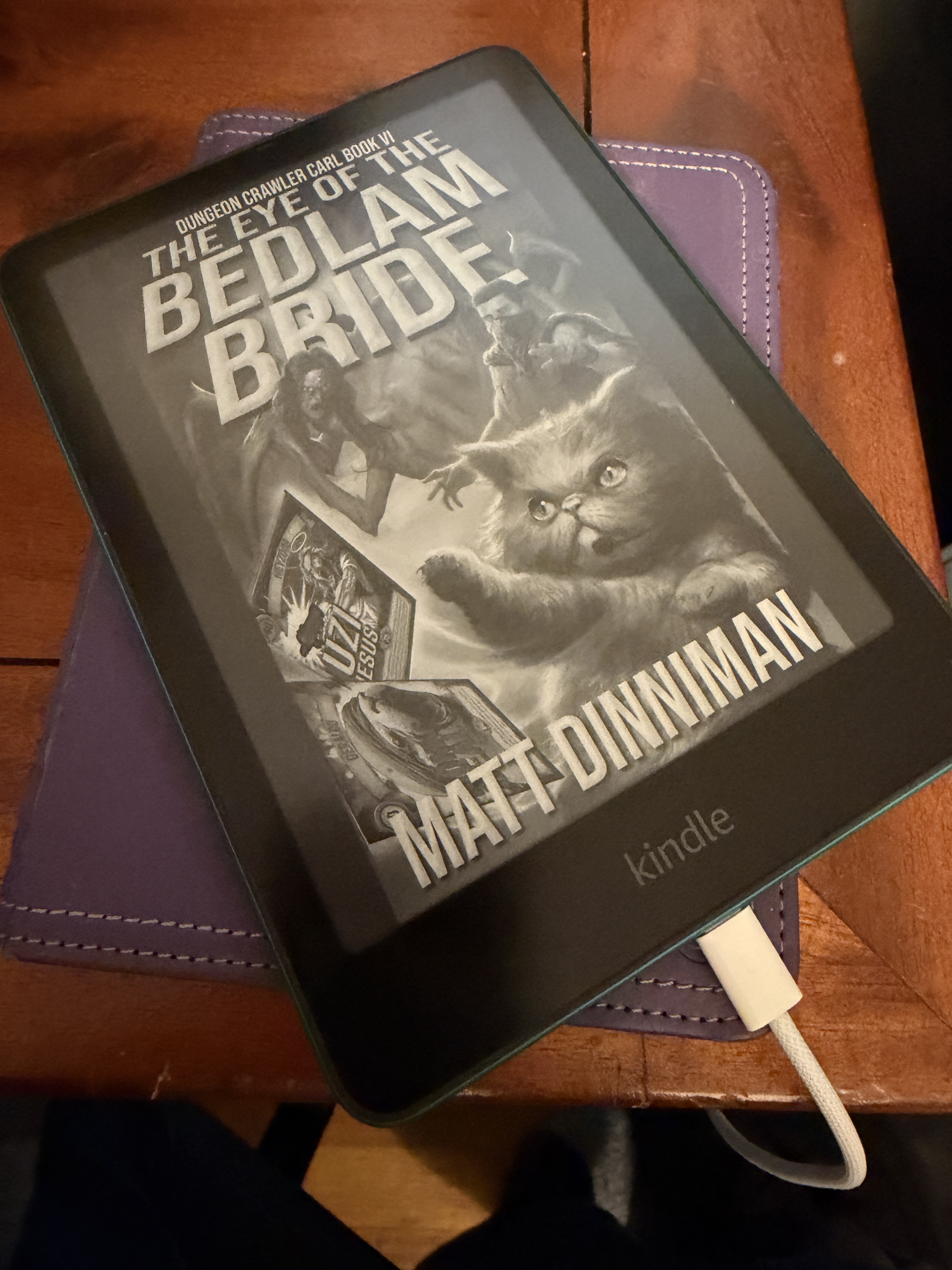

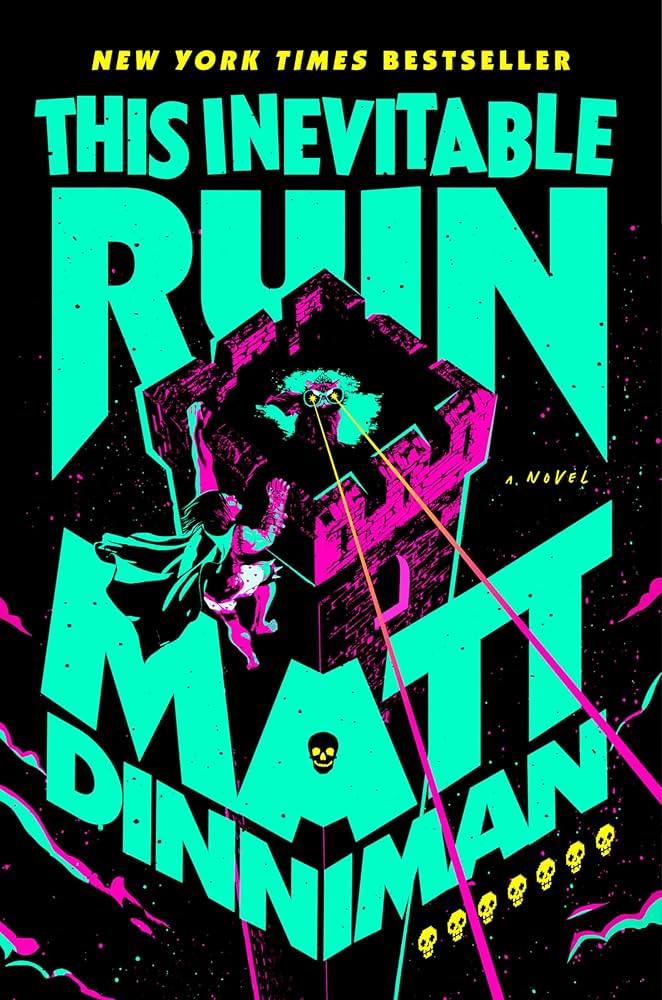

I finished the seventh and most recent book in the Dungeon Crawler Carl series last night, staying up too late to do it. The eighth book comes out in June; I pre-ordered it the literal first day it became available to do so. Dinniman has an unrelated book, Operation Bounce House, coming out in February, and I’ve preordered that as well. The series is currently expected to be ten books, and apparently might be eleven.

I don’t think I’ve reviewed any of the books as I’ve read them, and I don’t really intend for this to be a review yet either, as a multi-book review really ought to be for the whole series and even as fast as Dinniman seems to write, we’re at least two or three years away from that. I will say this, though: I started this series mostly out of FOMO, something that y’all know good and well catches me on books all the time. I don’t like not reading good books, even if their premise– aliens invade Earth and a guy and his cat get thrown into an intergalactic competition that somehow mimics the genre tropes of role-playing video games– is completely ridiculous. “LitRPG” is its own entire genre; having read and enjoyed eight books in it, other than reading more of Dinniman’s work in the future I have no plans at all to dip my toe into any other examples of it.

I’ve been reading about a book a month in this series since picking up Dungeon Crawler Carl in May. The first one was at least a little bit against my will; I wasn’t expecting to like what I was reading all that much, but again, FOMO.

I plan to restart the series in December so that I can have read it twice by the time A Parade of Horribles comes out. My wife picked up the first book on a whim a couple of months ago and is currently reading book five, and she’s read them back to back to back to back to back. Which means the same as “back to back” but sounds like more of a feat. This is not a thing she does, guys.

These books have no fucking right to be this good. They’re too ridiculous and too raunchy to be as good as they are. And yet somehow this series is the best new thing I’ve encountered in a long time, and having read four thousand pages of this series this year I am about to start over and do it again.

Plus Bounce House and the first book of another series of his called Kaiju Battlefield Surgeon, because right now Dinniman is tied with BrandoSando for the author I’ve read the most books from in 2025, and I can’t let Sanderson win that contest.

Just do it. Trust me. Put aside your reservations and pick up the first book. The whole series is on Kindle Unlimited if you happen to have Amazon Prime, so you don’t even have to pay for it. Get them from the library. I know, I know, this feels like it has to be dumb as hell. Go give them a shot anyway.