I’m not generally the type to gatekeep, but it’s not hard to find out whether someone is a Tupac fan or not. Ask them his birthday.

June 16th, 1971/ Mama gave birth to a hell-raising heavenly son/ See the doctor tried to smack me but I smacked him back/ my first words was thug for life, and Papa pass the Mac

That’s the first lines of Cradle to the Grave, the penultimate track from his album Thug Life, and … okay, you can be a Pac fan and not know that line right off, but I think more of us do than don’t. And I’ve taken a moment to myself on more June 16ths than not, since he passed away. Not a big thing, mind. Just a moment. But he made sure we all knew his birthday so I figure it’s worth remembering.

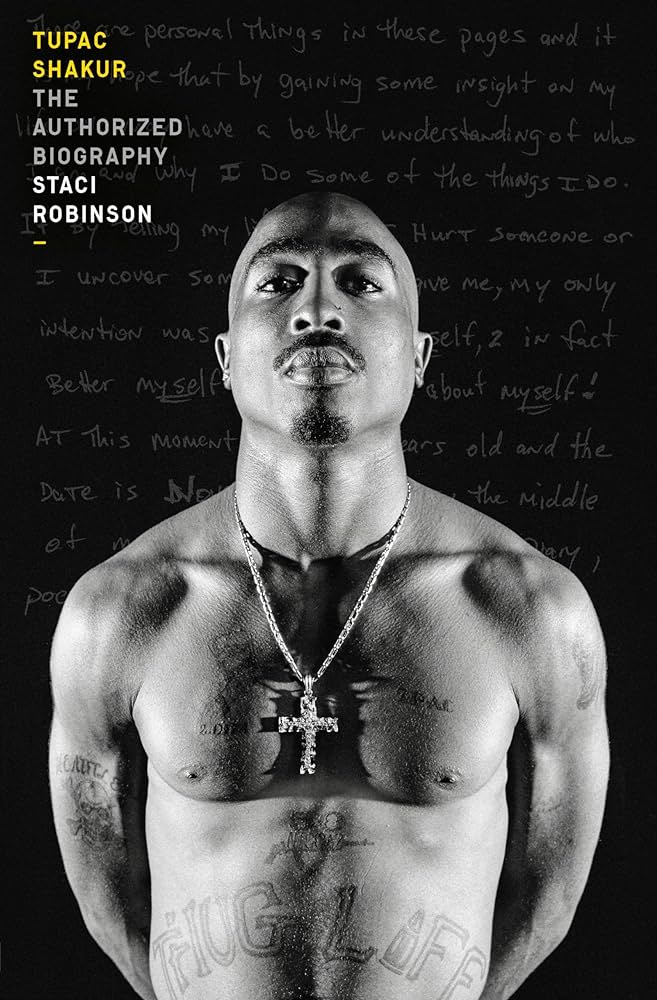

There have been a lot of words written about this man since his death. Take a look at Amazon; a search for “Tupac books” will provide you with half a dozen self-published books about him, mostly full of conspiracy theories, and any number of other works written by more, uh, authoritative entities. It was the words Authorized Biography on the cover that got me to pick this one up; turns out Tupac’s mother Afeni Shakur hand-picked Staci Robinson to write this book, which immediately gives it a hell of a lot more authenticity than the usual.

Part of me didn’t want to read it, to be honest. Pac is one of a very small number of people whose deaths made me cry. I don’t remember exactly where I was when I found out Kurt Cobain had killed himself. I don’t remember where I was when I found out Christopher Reeve or Stan Lee had passed. I remember where I was when I found out about Chadwick Boseman, but there were no tears. I remember exactly where I was and what I was doing when I found out Tupac was gone. I wasn’t completely certain I wanted to revisit everything, to be honest.

And the thing is, it’s not going to be that difficult to write a biography of Tupac Shakur that doesn’t properly respect him, “authorized” or not. Afeni Shakur died in 2016 so it’s not as if she was around to review the manuscript. A whole lot of people he was close to are gone, as a matter of fact. And … well, let’s be real. Pac was messy. At best. He wasn’t the violent, unrepentant criminal that the news media portrayed him as, but he had a hell of a self-destructive streak that was showing itself very early in his life and that he never really got control of as an adult, particularly in his last few years. If he hadn’t been shot in Vegas in 1996, the cops would have gotten him by now. There was never a universe where Tupac Shakur lived to die of old age, and he knew it.

It was a moment, the day when I realized I’d outlived him.

This is a worthy memorial to him, I think. Robinson had access to what must have been an enormous volume of Pac’s own writings dating back to his childhood– one thing I’ve heard about him from every single person who ever knew him is that the man was never without a notebook close to hand, and could shut out the rest of the world when he got something in his head that needed to be written down. I’m not going to dig up the video right now, but Shock-G tells a great story about Pac disappearing for a while, walking around looking for him, and finding him in the bathroom, sitting on the toilet, buck naked, and writing lyrics in a notebook.

The book is stuffed full of poems and fragments of lyrics and drawings and other writings, so many that I’m pretty confident that I’d recognize Tupac’s handwriting if you put it in front of me. It’s difficult to write biographies of writers and musicians, honestly, especially when they died young– it’s easy to fall into a rhythm of and then he wrote THIS, and then he wrote THAT, and sales charts and blah blah blah, and the book ends up in a lot of ways being a history of his intellectual development as much as anything else. He could have been one of history’s greatest intellects, born at a different time and in different circumstances. Robinson talks about his voraciousness for reading and his compulsive need to write in a way that, fifteen years ago, would have put me in mind of Thomas Jefferson and nowadays can’t help but remind one of Alexander Hamilton.

I never knew that he’d gotten married while he was in jail. Never knew that he’d dated Madonna, either, which I find hilarious. And I fell down a hell of a rabbit hole this afternoon when I realized that the book never mentioned Juilliard– I knew that he’d attended, but not graduated from, the Baltimore School for the Arts, which was where he met Jada Pinkett, who became a lifelong friend, but I thought that he’d attended Juilliard at least briefly. This story turns out to be false, and I’d love to know where the hell it came from– if you search for “Tupac Shakur Juilliard” you’ll find dozens of people confidently revealing that he’d gone there, often under a full scholarship, but Juilliard doesn’t seem to know about it, and it’s not mentioned on Wikipedia, and it wasn’t mentioned in the book. Pac never graduated high school, as it turns out, although he did eventually get his GED. I know I’ve told people that he went to Juilliard. I really do wish I had a way to track down the source of that story.

If I have a criticism of the biography, it’s that the book ends as abruptly as Tupac’s life did; he dies on the literal last page, and while I don’t think Robinson had any responsibility to get into any of the rumors and wild conspiracy theories about his death, especially once The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory(*) came out posthumously, I feel like something about the police (lack of) investigation and his legacy would have been warranted. His ashes are buried in Soweto, in South Africa. I didn’t know that, and I found out from Wikipedia today, not from this book. The man has released more albums since he died than he did when he was alive; I feel like one chapter in his book after his death isn’t asking too much.

That’s what I’ve got, though. No other real criticisms, and while I wasn’t initially sure I wanted to read this, in the end I’m glad I did. I haven’t taken the time to listen through his discography in a while, and I’ve been bobbing my head to Me Against the World while I’ve been writing this. All Eyez On Me is next, and that one needs to be LOUD, so I may need an excuse to take a drive for a couple of hours. We’ll see. In the meantime, this is well worth your time and money.

(*) If you really want to gatekeep Tupac fandom, ask somebody what the actual name of this album is, as I think most people just call it “The Makaveli album,” and I admit I just typed out The 7 Day Theory and had to stare at it for a minute to figure out what I’d left out.