I feel like I haven’t treated Tananarive Due with enough respect.

The Reformatory is the third of her books that I’ve read. I did not know that until just now! I remember reading her book My Soul To Keep way back in 2016, and at the time I really liked it, but for some reason every time I think of it now I feel like it wasn’t something I enjoyed. And I just discovered that I read her debut novel, The Between, in 2020.

When I tell you that I don’t remember anything about that book, I need you to understand that not only do I not remember any details about the story, I did not even remember the book existed. That cover looks unfamiliar. I cannot picture where my copy of it is in my house, and I surely read a print copy. I don’t know what the spine looks like. If you had asked me ten minutes ago what the name of Tananarive Due’s debut novel was, I would not have been able to tell you. My recall of books from years ago is not always great, I admit that, mostly because I read 100+ books a year. But forgetting a book existed or that I ever read it at all is not a thing that I do.

And that after my weird about-face on My Soul to Keep? I have no explanation for this phenomenon.

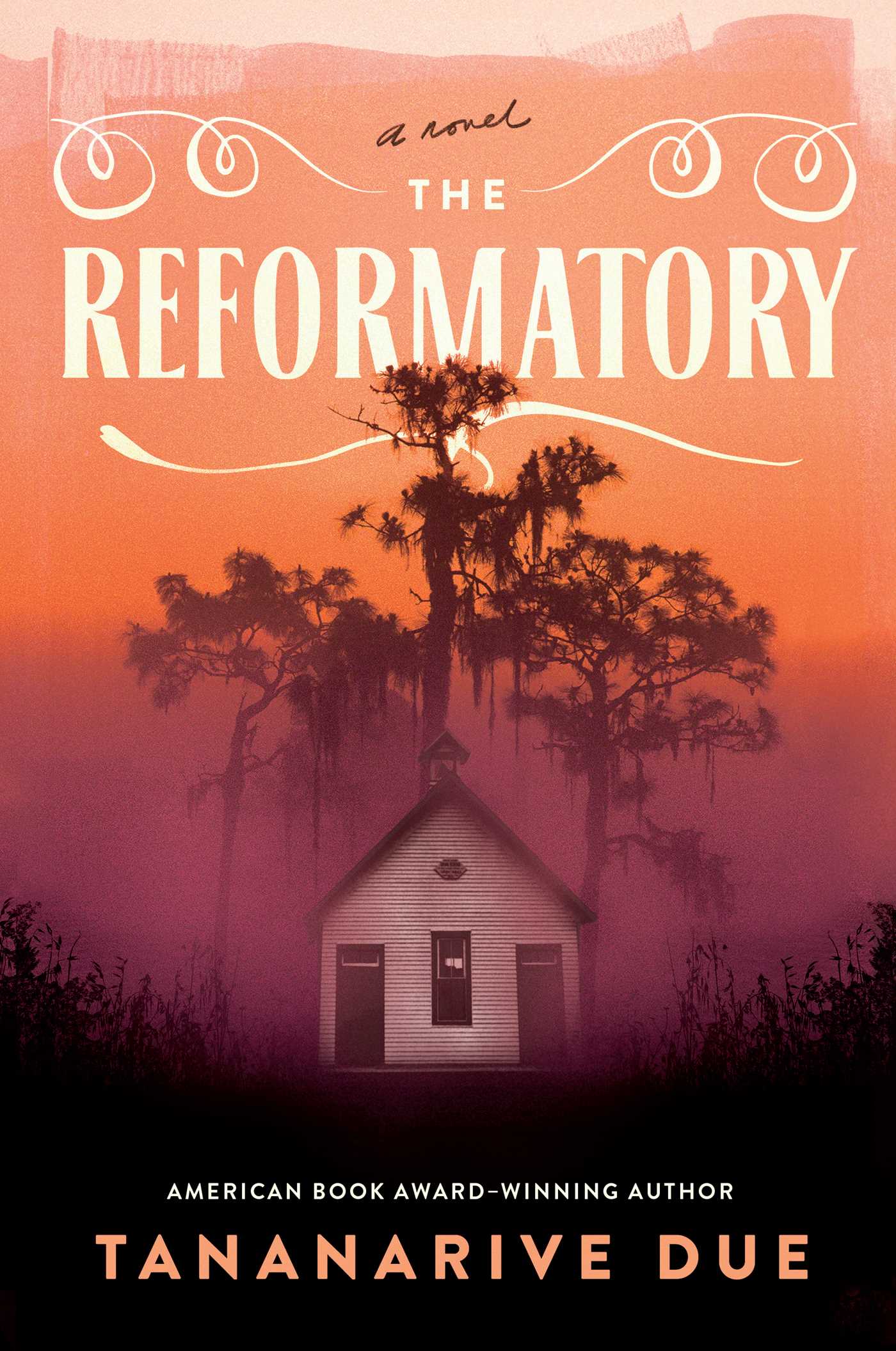

Anyway, The Reformatory is really good, and if six months from now I find that I’ve turned on it too, I’m gonna need someone to come get me.

The Reformatory is the story of Robert Stephens Jr., a 12-year-old boy who is sent to the Gracetown School for Boys for a supposed six-month sentence after kicking the son of a wealthy white man in the knee. The book is set in 1950 in Florida, thick in the middle of Jim Crow, and the Gracetown “school” is a segregated, haunted nightmare, run by a grotesque abomination of a man. It is widely understood that Robert won’t be getting out in six months, as the warden is renowned for finding excuses to hold on to any boy sent to him until their 21st birthday regardless of their original sentence. Beatings and torture are commonplace and the inmates prisoners “students” are encouraged to turn on each other at any opportunity.

The book bounces back and forth between Robert’s story and his sister, who Robert was defending when he kicked the other boy. She is trying her best to get him released, which is easier said than done in any number of ways. Their father has fled to Chicago after his attempts at unionization upset the Klan, and it’s fairly clear that part of the reason Robert is being treated as poorly as he is is because the authorities can’t get at his father.

The book would be scary enough without the haints, is what I’m saying, and the presence of a large number of ghosts at Gracetown becomes almost a distraction from all of the more grounded evil taking place there. Of course, a number of them are ghosts of children who were murdered or otherwise died while incarcerated there, and, well, a whole bunch of them bear quite a serious grudge against the warden.

I won’t go into much more detail, because (as usual for books I enjoyed) you deserve to experience the twists and turns on your own, but this really is a hell of a book, and I’ve not heard a lot of people talking about it. Give it a read.

You may not be aware of who Rev. Ralph David Abernathy is, but I guarantee you know his face. Why? He’s the guy standing just behind or just to the side of Martin Luther King, Jr. in every picture of Martin Luther King ever taken. In many ways he was as influential to the civil rights movement as King was– he was even the guy who brought King in as the visible face of the movement during the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was what made MLK a national figure– but because he was so often quite literally the guy behind the guy he’s not nearly as well known.

You may not be aware of who Rev. Ralph David Abernathy is, but I guarantee you know his face. Why? He’s the guy standing just behind or just to the side of Martin Luther King, Jr. in every picture of Martin Luther King ever taken. In many ways he was as influential to the civil rights movement as King was– he was even the guy who brought King in as the visible face of the movement during the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was what made MLK a national figure– but because he was so often quite literally the guy behind the guy he’s not nearly as well known.