So let’s imagine that you’re in charge of a school. Or, hell, an entire school district, since for the purposes of this conversation I’d prefer that there be some notion of a wider community that has to be served by your school.

So let’s imagine that you’re in charge of a school. Or, hell, an entire school district, since for the purposes of this conversation I’d prefer that there be some notion of a wider community that has to be served by your school.

Which is more important: serving the needs of each individual student, or serving the needs of your community as a whole? And what happens if those needs conflict with one another? What if you literally cannot serve the best needs of the individual student if you’re going to focus on serving the needs of your community?

Think about that while I provide some background and tell a couple of stories. Also be aware that I still have an intense goddamn headache and probably should not be staring at a screen or trying to think straight right now, so if this seems incoherent I apologize in advance. 🙂

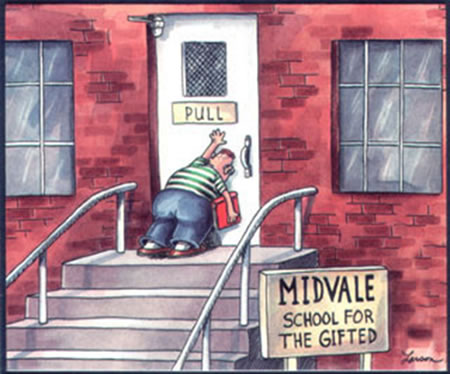

When I was in fifth and sixth grade my school corporation piloted a new honors program. (Incidentally, I work for this district now.) High achieving students from across the corporation were pulled out of their home schools and put into two classrooms in the same building. That building, as it turned out, had previously featured some of the lowest, if not the lowest, test scores in the corporation. A year later, having literally imported the fifty or sixty smartest fifth and sixth graders available to them (and, presumably, displaced some of their other students to make room for us, although we were stuck in a portable classroom in the parking lot for sixth grade) the corporation made much hay about how the building had been turned around.

The building hadn’t been turned around. They’d just played with the numbers a bit. The classes were supposed to be educationally innovative, piloting all sorts of new ways to teach. I do not recall learning much in fifth and sixth grade. I do recall my mother constantly struggling with the principal– who, incidentally, is one of my district-level supervisors now. For whatever it’s worth, she appears to have positive memories of me.

This was an early lesson for me on 1) how to lie with statistics, and 2) the cynicism embedded into standardized tests. Note that this was in the mid eighties and thus way predates our current obsession with standardized testing.

Note also that my parents enthusiastically registered me for this program when the opportunity became available and that I, furthermore, was super psyched about being in it, despite having just had what was probably the best year of my school career in a school I loved in fourth grade. Nobody had to talk anybody into anything here.

Fast forward to now: my corporation has an honors academy at the middle school level. This is the program I was in in fifth and sixth grade writ large. Note also that the “honors academy” is the largest middle school in the corporation, with, I believe, nearly twice the students that my building has. Note that again, since these kids are all at the honors academy, that means that they’re not in my building or any of the other schools.

I could complain about this building quite a lot, if I wanted to. As an educator, I hate them. They win virtually every corporation-level competition that exists; it turns out that if you pack a building with high-functioning kids with active, engaged, and generally wealthy parents, you get things like great sports programs as a side effect. Nobody else can compete. The entire rest of the corporation is basically competing for second place.

Now reflect upon the fact that my building (and every other building in the corporation) is still expected to pass the same number of kids on the ISTEP as every other school in Indiana, despite the fact that, give or take, 20% of my highest-functioning, highest-scoring kids are taken from my building and sent to this other school, and that furthermore we lose additional kids to this school every year. Last year, for example, nineteen kids from my school with passing or high-passing ISTEP scores transferred to this other building.

We are, effectively, expected to achieve average results– but with the top 20% of our distribution sliced off and sent somewhere else. And it happens every single year. And they are expanding this other school, adding new classrooms every year for the next three or four years– so it’s only going to get worse.

Note that I cannot challenge the decisions of any of the individual kids or the individual parents. My parents, and I, made the exact same decision when I was in fifth and sixth grade, and frankly would probably do so again.

Note that this individual decision, made enough times, basically means that achieving “average” results becomes mathematically impossible.

(One of the solutions to this is to work with a growth model rather than caring about pass rates. I’ve talked about this before; I don’t think the ISTEP should even have a passing score. But that’s not the world I live in at the moment.)

In the last couple of weeks, I’ve gotten both my ECA (End of Course Assessment) results and my ISTEP scores back. I was initially a little depressed with my ECA scores– a high school graduation test that is given to my honors 8th graders– until I looked at previous scores for my building and realized that I’d managed the highest pass rate the school has ever had. I literally passed three times as many kids as a couple of years ago.

My ECA scores, in other words, make me look like a genius.

I got my ISTEP scores back yesterday. ISTEP scores are tricky; an essential part of the scores (the growth model part) don’t get released until a bit after the raw scores, and the raw scores can be a bit misleading if you’re not careful about how you look at them.

My honors kids– the same kids that had the record-setting ECA scores– did great, and were more or less in line with the improvement numbers I’ve seen in years past. Keep in mind that in the last two years I had the best improvement numbers in the building one year and either took second definitively or tied for second, depending on the metric you’re using, in the second year.

My regular ed kids did terrible. My seventh graders barely moved at all. I have a couple of pockets of success here and there– I had four kids who I was really hoping for passing scores out of, who have never passed before– and I got two out of the four and the third kid held on to what was frankly a staggering score increase from last year, but still didn’t quite pass. But on average my seventh graders were basically exactly where they were last year. (This phenomenon doesn’t appear to be limited to me, by the way– everyone I’ve talked to is shocked by how the 7th graders did.)

So, I’m gonna be evaluated on these test results, right? Do we look at the honors kids, and conclude that I’m a stellar educator? Do we look at the seventh graders, and conclude that I’m terrible? Or do we look at an average of both, and conclude that I’m merely mediocre?

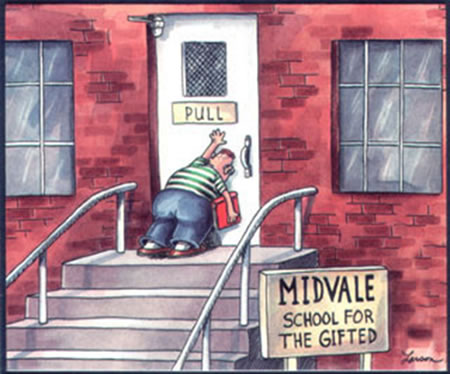

Here’s the problem with honors classes: by concentrating the kids who do best into individual classrooms, you by definition take them out of regular ed classrooms. Which has the effect of concentrating special ed students, low-functioning but not quite special ed students, kids who could do well if they wanted but simply don’t give a shit, and– worst of all– behavior problems into all of your other classrooms. Which means that the kids who either don’t care or are actively invested in being destructive have a much easier time of taking over and destroying your class for the kids who do care.

I had two different results with these two classes. My first and second hour, while the kids are mostly bright (although some of them clearly don’t want to be) is overrun with behavior problems and has been all year. My third and fourth hour kids are mostly– understand that this is not an exaggeration– either special education kids or criminals. Fully 20% of third and fourth hour spent some time this year either expelled from school or wearing ankle monitors. I have four different students in that class with sub-60 IQs. My best students in that room wouldn’t even qualify as average in my other class.

It turns out that I’m a much better teacher when I get to, y’know, actually teach. My third and fourth hour cratered on the ISTEP. It turns out it’s really goddamn difficult to get math concepts through to kids when half of them don’t give a shit and the other half require individual attention. That class had other adults in it for the entire school year but even with three people in the room there are simply too many kids who need help for us to be able to actually do our jobs adequately with all of the kids– particularly when there are three or four at any given time who will literally do nothing if an adult is not standing next to them monitoring them at all times.

Now, none of these kids change if I introduce our honors kids back into the classroom with them. But you know what happens? They actually see success. I can ask questions of the classroom and have somebody who is going to answer. The number of times I’ve asked 3rd and 4th hour simple shit this year and gotten nothing but blank stares because half of them don’t know, half of them don’t care, and 2/3 of them are waiting for someone else to answer beggars belief. And, furthermore, it increases the resources available to the kids who need help– if you can ask TJ how to do a problem and expect to receive a coherent answer, rather than him just saying “it’s 3” (and honors kids generally want to be helpful to other students rather than just letting them copy) then you don’t have to ask me. I can concentrate my efforts on fewer kids, which means that more of them actually get educated on any given day. Which means that, overall, my building looks better and more of our kids are getting the educations they deserve.

What I can’t do as well in those circumstances– and maybe this means I’m just not good enough at differentiating my instruction; don’t get the idea that I’m trying to put all the blame on the kids here– is push the honors kids. See the problem? Getting rid of honors classes requires a collectivist mindset from both the parents of those honors kids and the students themselves. If I don’t have that honors Algebra class, well, I can’t teach anybody honors Algebra, now, can I? I can do individual enrichment but that’s not remotely the same as an entire directed class.

Which means that those parents and those kids have to decide that the education for everybody is more important than their own education. And I cannot criticize anyone for not being willing to make that decision.

After all, I didn’t make it myself, did I?

Bah.